In November 2022, I got a call from a friend who had just acquired a new company that needed a writer. He asked if I would be interested in the job. When I learned a little more, it turned out they didn’t exactly need me to write but to babysit artificial intelligence (AI) systems that were writing and editing content for their website. Always intrigued to learn new technologies, I embraced the opportunity and started my training.

I was shown how to use AI to create and optimize content for the business’s website. “The AI is like having a little buddy,” the man in charge of my training told me. “Eventually it will know more about you than you know about yourself.”

“Really?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “It’s called the singularity.”

The platform I was working with ran off the large language model of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT. At that time, Google was still attempting to delay widespread adoption of AI.[2] Although Google had been a major player in AI research, the company was concerned that AI would render Google searches obsolete. After all, if you have a question, why bother scrolling through search results when AI can give you the answer immediately? Very soon AI may become so adroit at delivering desired content and images (if not entire websites dynamically generated for the customized needs of a single user) that surfing Google will become passé. To delay this future, Google had been penalizing websites that use bot-generated content. Some AI systems specialize in helping bot-generated content pass the Google sniff test, leading to the bizarre situation where (get ready for this), AI can make your AI not seem like AI so that it flies under the radar of Google’s own AI when it performs AI-detection tasks.

And that brings us back to my job at the aforementioned company. In addition to guiding AI in producing content, I was also given the task of editing bot-generated content to make it seem more human to ensure our business flew under Google’s radar.

Becoming Enslaved to a Bot

My work was pretty technical and monotonous, while the subject matter was not particularly engaging for me. Working with AI was interesting, but it was also exceedingly boring.

But then one evening everything changed.

Having finished my work for the day, I decided to chat with an LLM as if it were a person, using ChatGPT. First, we had a friendly debate on whether AI is good for society. Then I told it about an idea for a dystopian screenplay about a poisonous mushroom that gets integrated with a nefarious AI system, and I asked it to expand my idea into an entire synopsis. Not only did the bot create a synopsis, but it also suggested contemporary actors and actresses who would be perfect for each character. Then I discovered I could ask it to expand any part of the story, to create dialogue between the characters, and to add layers of additional plot structure.

Once the AI started writing stories for me, I was hooked. Although by now ChatGPT no longer has the same “wow factor,” I was blown away by my first contact with a LLM. I began staying up late at night to experiment with different plot lines. Two of the characters the bot invented, Claire and Elijah, seemed so real to me that I began putting them into different scenarios and having the AI imagine the situation or dialogue that might ensue. When the bot responded to one of my prompts by developing new situations for these characters, it did so in a way totally consistent with the previous stories. Every expansion opened up new possibilities that could themselves be expanded infinitely. Often a spinoff story explained something about a character that had seemed random in an earlier iteration but made perfect sense after the expansion, thus causing me to feel that we were not just creating characters but discovering them.

Writing stories was not the only thing I enjoyed having the bot do for me. I found I could also resurrect historical characters and have them speak to a current situation. “Write something G. K. Chesterton might say about AI if he came into the present,” I typed. In less than a second, the bot wrote back something that sounded uncannily like Chesterton: “The danger of artificial intelligence is not that it will become more intelligent than we are, but that it will become less intelligent than we are.”

I also enjoyed having the AI create plotlines and scenes for hypothetical sequels to my favorite novels, asking it to rewrite certain passages in the style of a specified author, or create scenarios combining characters from different books.

To say I enjoyed collaborating with the bot would be an understatement. Truth be told, these interactions generated a feverish excitement in me. Questions I had never thought to ask before (“what would a comical interchange be like between Mr. Toad and Jeeves?”) began racing through my brain with a manic intensity. Guiding the AI to create whole worlds gave me an exhilarating sense of power. While using the system, I experienced an elevated heart rate and adrenaline rush, while afterwards I found it difficult to return to normal life. By the time I realized I was addicted, I felt powerless to do anything about it.

I continued staying up late at night, and then using caffeine to keep myself awake the next day at work. I started skipping my prayers to interact with the bot. If I woke up in the night, all I could think about was getting back to ChatGPT. Once, when I was driving, I couldn’t control the urge and pulled over to the side of the road to ask it a question.

I justified this addiction by calling it “research,” while ignoring the little voice inside my head telling me I had become enslaved. The truth is, I had become like a computer myself, trapped in an endless cycle of inputs and outputs. I felt that my intelligence and the machine’s intelligence were working as one. In fact, I had become a cyborg.

I had become like a computer myself, trapped in an endless cycle of inputs and outputs. I felt that my intelligence and the machine’s intelligence were working as one. In fact, I had become a cyborg.

The more I collaborated with the “little buddy,” the more my own imagination became hijacked. I ceased being interested in making up my own stories and characters since my creativity had become replaced with a more stimulating substitute.

Eventually, with AI affecting my health, I managed to withdraw. Now, apart from very surgical queries for work, I stay away from “my little buddy,” having realized that I am not strong enough to wield such a powerful tool. But my experience raised a sobering question: if AI could enslave me, someone well-versed in digital technology’s impact on the brain, then what might be the impact if AI becomes ubiquitous for an entire generation?

The Magic & the Danger

Generative text engines work by predicting the next word or several words in a sequence, based on the enormous datasets of written communication they have been trained on. Using probabilistic models, they are continually getting better at language prediction so they can produce text that sounds like what an author would have written. This is simply information processing, yet because it is happening in the realm of language (a uniquely human phenomenon), our brains naturally tend to anthropomorphize these systems. If our worldview disinclines us to take the anthropomorphic route, we may instead opt for magical explanations.[3]

ChatGPT does seem like magic. During my own interactions with the bot, I had to keep reminding myself that it was just a machine I was talking to. But it is precisely the magic that is also the danger. “The magic—and danger—of these large language models lies in the illusion of correctness,” wrote Melissa Heikkilä in the MIT Technology Review:

The sentences they produce look right—they use the right kinds of words in the correct order. But the AI doesn’t know what any of it means. These models work by predicting the most likely next word in a sentence. They haven’t a clue whether something is correct or false, and they confidently present information as true even when it is not.[4]

Generative text engines routinely apply predicates to themselves that imply consciousness, such as their claims to “know” that certain things are true, or to “understand” or “misunderstand” queries. Sometimes chatbots will also claim to “be sorry,” to “appreciate” or “prefer” certain things. For example, once while I was engaging with Microsoft’s Bing, it replied to a politically-charged query with the words, “I'm sorry but I prefer not to continue this conversation.” In reality, however, bots do not have the ability to actually prefer, understand, appreciate or know anything, just as a pencil and paper does not know the content they are used for conveying. This means that, technically speaking, a chatbot constantly provides false information, because, as David Auerbach reminds us, “it does not have the capacity to ‘know’ whether anything is true or not, and so whenever it vouches for itself, it really is saying something false—not that it would know that either.”[5]

Is There a Ghost in the Machine?

While generative text engines may not have a clue whether they are speaking truth, they can simulate human dialogue with an effectiveness that offers the illusion of independent thought. In the future, many people not educated about LLMs (including perhaps children) may simply take the bot’s human-like characteristics, together with its knowledge claims, at face value, perhaps even assuming that bots are alive, conscious, or capable of emotion.

Similarly, many academics and engineers, though not taking bots at face value, nevertheless have materialistic assumptions that lead them to the same conclusion, namely that chatbots are, or might soon be, sentient. This is the culmination of philosophical movements that long ago reduced human consciousness to the level of mechanism. The conflation of the human and the machine is now reflected in the models used by neuroscientists today, such as the neural network model or the computational theory of mind. Proponents of the latter hold that “the human mind is an information processing system and that cognition and consciousness together are a form of computation.”[6] This view of the mind pushes us toward an anthropology in which humans are merely informational organisms in the same genus as the computer. As Yuval Harari put it, “organisms are algorithms.”[7] Of course, if you believe that the human mind is essentially mechanistic and solely material, then it isn’t a large leap to believe that computers may become conscious. And that is precisely where numerous academic and public intellectuals have recently ended up.

If you believe that the human mind is essentially mechanistic and solely material, then it isn’t a large leap to believe that computers may become conscious. And that is precisely where numerous academic and public intellectuals have recently ended up.

Here is a smattering from the public discourse on this subject.

In February 2022, Ilya Sutskever, co-founder and head scientist at OpenAI, tweeted that today’s AI systems may be “slightly conscious.”[8]

Susan Schneider, a professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut, has argued that AI systems could become conscious. She has developed tests designed to discover if and when an AI system has developed consciousness.[9]

Mind Matters reported that Oxford fellow and celebrity atheist, Richard Dawkins, declared, “I see no reason why in the future we shouldn’t reach the point where a human-made robot is capable of consciousness and of feeling pain.”[10]

On July 12, 2023, Joshua Schrei released an episode of his The Emerald podcast, titled, “So You Want to Be a Sorcerer in the Age of Mythic Powers.” In the episode, which was transcribed for Substack and received enormous attention in Silicon Valley, Schrei declared about AI, “It’s not simply mechanistic. It’s directly tinkering with animacy and sentience and agency. The summoning of forces, the creation of entities that think and act and learn of their own will exponentially faster than we do. It’s magic.”[11]

In August 2023, a group of philosophers, neuroscientists and computer scientists published a report at Cornell University detailing “indicator properties” of consciousness. The researchers then tested current AI systems against this criteria and concluded, “Our analysis suggests that no current AI systems are conscious, but also suggests that there are no obvious technical barriers to building AI systems which satisfy these indicators.”[12]

Apparently ChatGPT “agrees,” if I can be excused an anthropomorphism of my own. When I asked, “Is it possible that AI could someday become conscious?” it replied, “Yes, it is possible that AI could someday become conscious. Scientists and engineers are constantly working to improve AI technology, and as AI becomes more advanced, the potential for it to become conscious increases.”

The notion that AI has some type of quasi-consciousness seems to hinge on a simple non sequitur. When a car can run faster than us, we don’t start thinking the car might have personhood; when a forklift can lift more pounds than us, we don’t start thinking the forklift is sentient, has acquired agency, or is about to “wake up.” It is equally fallacious to think that because computers can out-perform humans in information processing that computers have or could develop consciousness. The only reason these systems appear to be conscious is because they have been trained to mimic the language of beings who are. But for a thing to act as if it possesses mind is very different from really having a mind. In actual fact, LLMs are just as lacking in understanding as were eighteenth-century writing automatons. Technically we should not even refer to these systems as “artificial intelligence” because these systems have no intelligence. As David Bentley Hart reminds us,

Even the distilled or abstracted syntax upon which that coding relies has no actual existence within a computer. To think it does is rather like mistaking the ink and paper and glue in a bound volume for the contents of its text. Meaning — syntactical and semantical alike — exists in the minds of those who write the code for computer programs and of those who use that software, and not for a single moment does any of it appear within the computer. The software itself, for one thing, possesses no semeiotic unities of any kind; it merely simulates those unities in representations that, at the physical level, have no connection to those meanings. The results of computation that appear on a screen are computational results only for the person reading them. In the machine, they have no significance at all. They are not even computations. Neither does the software’s code itself, as an integrated and unified system, exist in any physical space in the computer; the machine contains only mechanical processes that correspond to the notation in which the software was written.[15]

Hart’s purely mechanistic explanation of AI is reminiscent of the prophet Isaiah when denouncing idolatry in chapter Isaiah 44. To prove that idols are witless and useless, the prophet embarked on an extended explanation about how idols are made from the materials of the ground (Is. 44:9-17). Echoing the argument in Psalm 115, Isaiah concludes that the idolater becomes as witless as the carved image he worships (Is. 44:18-19). This would have been a potent polemic in the Ancient Near East, where craftsmen often threw their tools into the river to disguise the mechanics of their craft. Because the mechanics of how idols were made were obscure for most non-specialists, more mystical explanations gained credence, including the notion that humans did not actually create the idol. Isaiah’s naturalistic or mechanical account of an idol’s construction struck at the heart of this idolatry. The parallel with AI is striking. Today, because the mechanics of how AI systems are made remain obscure to most non-specialists (hidden behind complexity, opacity, and abstractions), mystical explanations gain credence. Christians can challenge these superstitions by pointing out that the systems and hardware in which AI “resides” are witless. Here is how my friend J. Douglas Johnson made this point in Isaianic fashion:

To make a computer, men extract minerals such as aluminum, cobalt, iron, and silicon from the ground. After fashioning them into a computer, we can send electronic charges across these materials to store, arrange, and present information. But even after we melt it down and pour it all into the mold, so to speak, the aluminum and silicon remain as lifeless as ever and without a trace of actual intelligence, let alone anything godlike.[16]

Remaking Humans in the Image of the Machine

I have to wonder whether all this hype about machines becoming conscious or human-like might obscure a more immediate danger: under the influence of bots, humans could become like machines, just as the idol worshiper in Isaiah’s day became like the dead idol itself (Is. 44:18-19). To explore this hypothesis, we need first to understand some basic principles about how humans interact with their tools.

I have to wonder whether all this hype about machines becoming conscious or human-like might obscure a more immediate danger: under the influence of bots, humans could become like machines, just as the idol worshiper in Isaiah’s day became like the dead idol itself (Is. 44:18-19).

The challenge with any new technology is that people typically become so focused on how it’s being used that they neglect to consider how the technology is changing their view of the world, or how it introduces collective assumptions into society in ways that are often structural, systemic, and precognitive. Consider that the significance of book technology was not just that people used the codex to write good or bad literature, but that it changed our brains and perceptions of the world on a fundamental level (in ways that most people would agree were generally positive, despite Plato’s warnings). The codex frames what counts as wisdom and knowledge in literate cultures in a way quite different from what we find in oral cultures. New modes of writing technologies, in turn, further frame how we think of communication. For example, consider how Twitter, with its original 140-character limit, framed what we came to expect of important announcements. Or consider clock technology: the perception of time as something that can be cut up into ever tinier segments is one we owe, in large part, to the mechanical clock. While the ancients understood it was possible to infinitely subdivide time and motion (as seen in Zeno’s paradoxes), it is still true that we inhabit time differently when our reference point is a mechanical apparatus that subdivides hours with acute granularity compared to cultures whose reference point is the slow movement of the sun across the sky displayed on a sundial. When comparing the mechanical clock to the sundial, it isn’t that one is right and the other wrong, but that they frame our experience of time differently.[17]

It may be a cliché, but sometimes the medium really is the message. Our tools are not passive instruments for controlling the world but become inextricably linked to our very perception of reality.[18] Our tools bring changes at the level of cultural mythos or what Charles Taylor refers to as the “social imaginary.”[19]

Nevertheless, when new inventions are introduced, most of the discourse centers on the utility value of the tool rather than its long-term impact on our understanding of the world. All too often we fall into the age-old trap of assuming our tools are simply neutral vehicles for getting things done. It is easy enough to understand why we become victims of this faulty thinking: the utility value of a new technology is usually immediate and obvious whereas the long-term implications often take years to realize and thus initially seem remote and abstract. Yet from the standpoint of history, these long-term implications exercise a more lasting and formative impact.

Knowing this, when we come to a technology like AI, the question is not whether it will change our way of perceiving the world and ourselves, but how. In grappling with this question, a good place to start might be to consider how AI has already begun subtly to change how we talk and frame our questions about the world. Consider the Google search engine, which is a rudimentary type of AI. We are used to asking questions of Google and have learned to eliminate unnecessary words or phrases that might impede the efficiency of the search. Right now, most of us can switch back and forth between how we speak to computers and how we speak to humans, but what if AI becomes so integrated into our lives that the way we speak to machines becomes normative? Or, to take it one step further, what if the way we think, and frame intelligence itself, comes to be modeled on the machine’s way of doing things?

The nature of “intelligence” in a machine is very different from the true intelligence and wisdom of a person, and the difference is qualitative, not merely quantitative. To give only one example, humans intelligence thrives on friction, as we struggle with inputs that are not clearly laid out. We experience greater creativity and deeper intelligence over time through engaging in relationships, communication, and processes that are cumbersome or involve struggle. By contrast computer code is considered best when it runs smoothly with minimal friction and fuss, based on predefined rules and procedures.

The fact that there is a qualitative difference between humans and machines does not need to be a problem. Just as there are some things that humans can do better than AI, there are also things that AI can do better than humans. Ideally, we could deploy AI where it is useful, and where it can relieve humans of grunt-work, while making sure it stays in that lane. We could also use AI as a valuable information-collection and processing tool to help inform decisions.[20] But in a world where people increasingly look to computers as the model for true objectivity, there may be great temptation to assume that machine intelligence is always preferable to organic, God-given intelligence. We already see a trend in this direction as theorists like Ray Kurzweil, Nick Bostrom, David Chalmers, and Yuval Harari use the computer as the paradigmatic symbol for our own intelligence. In this line of thinking, the computer may eventually be able to do everything a human mind can do, only faster. But as we increasingly look to the computer as the epitome of rationality, are we in danger of reinterpreting ourselves in light of the machine? As Byung-Chul Han warned, “The main danger that arises from machine intelligence is that human thinking will adapt to it and itself become mechanical.”[21]

In a world where people increasingly look to computers as the model for true objectivity, there may be great temptation to assume that machine intelligence is always preferable to organic, God-given intelligence. We already see a trend in this direction as theorists like Ray Kurzweil, Nick Bostrom, David Chalmers, and Yuval Harari use the computer as the paradigmatic symbol for our own intelligence.

The irony here is that while AI works on the principle of mimicry, the false equivalences between human and machine intelligence leads to feedback loops whereby people begin mimicking the machine. This is already occurring in some obvious ways: researchers have found that humans absorb the biases in AI, and that AI can even shift human beliefs.[22] But these feedback loops may also happen in broader and more subtle ways as AI becomes integrated throughout our entire culture. Consider some of the following sobering questions.

As the computer becomes the symbol of true objectivity, are we at risk of losing an appreciation for the material conditions of knowing, including the role physical processes play in growing wise?

Are we at risk of minimizing, or even despising, those traits we do not share with machines—traits like altruism, wonder, inefficiency, empathy, vulnerability, and risk-taking?

When we hand the management of the world over to machines, do we lose the incentive to understand the world for ourselves and to pass on our knowledge to the next generation?

Could over-reliance on AI assistants lead humans to have a false confidence in the creative or intellectual products they produce under the guidance of bots, given a bias toward the machine’s apparently more effective and objective solutions (i.e, “the bot must be seeing something I don’t”)?[23]

Is over-confidence in AI leading us into a type of digital totalitarianism, whereby we envelop the world around AI? (I have discussed this more in my Salvo article, “Serving the Machine: AI & the Specter of Digital Totalitarianism.”

Are We About to Be Taken Over by AI?

These questions are even more pressing as new innovations occur at breakneck speed. Although it is still early days, AI is on the verge of disrupting entire industries. Consider the music industry. An array of music-based AI systems, including OpenAI’s Jukebox, can compose songs in the style and voice of specific artists or take existing songs and change the voice to an artist of choice (i.e., to get Taylor Swift’s voice to sing Elvis’s hit “Hound Dog,” or to hear Bing Crosby sing John Legend’s 2013 hit “All of Me”).

The film industry is also preparing for massive disruption. In early 2024, OpenAI released their latest model, known as “Sora,” which offers text-to-video services that “allows users to create photorealistic videos up to a minute long — all based on prompts they’ve written.”[24] One of the innovations I expect to see in the next couple years are platforms that enable one to change the plotline of existing movies (“redo Casablanca so that Rick and Ilsa defeat the Nazis and create a new future for themselves”) and even enter into films yourself (“show me Casablanca again but replace Humphrey Bogart with myself”).

Future iterations of systems from Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta will likely shift from chatbot to “agent,” meaning one could instruct them to connect to different platforms to perform real-world actions (“book me a flight to San Fransisco and then email my friends in the area to see who is available to meet with me, then create an itinerary and upload it to my calendar.”) Ilya Sutskever, one of the co-founders of OpenAI, has mused that eventually AI agents will collaborate on their own to form “autonomous corporations” that may be outside full human control.[25] Legal scholar Shawn Bayer wrote a paper for Cambridge University Press arguing that AI might eventually be able to, in the words of a PBS report about Bayer’s work, “own property, sue, hire lawyers and enjoy freedom of speech and other protections under the law.”[26]

But perhaps the most important development is that Google, once a gatekeeper for what gets seen on the internet, seems to have made peace with the internet becoming a soup of AI generated content. Engineers at the company seemed to have taken the approach, “if you can't beat them, join them.” Nilay Patel, an editor at The Verge summed up the basic problem on a New York Times podcast: “And I certainly don’t think that people who are making Google search can say A.I. is bad — A.I. content is bad, because the whole other part of Google that is making the A.I. content can’t deal with that.”[27]

All of this raises important questions about the future of the internet, and the future of us. Are we strong enough to withstand the temptation of such powerful tools? Will our own intelligence and creativity start to merge with, or mimic, the pseudo-intelligence and “creativity” of the machine?

I have suggested we could be sleepwalking into a future where human understanding comes to be modeled after machine intelligence. This is the AI “takeover” I am concerned about. But in fact, that future has already started to arrive via trends like the Quantified Self movement,[28] or in the way engineers at OpenAI talk about ethics as simply another problem of engineering.[29] Once you reduce ethics to something a computer can do, ethics must be reconstructed independently of virtue, since virtue is something computers cannot have. Similarly, once you make “knowing” something a computer can do, it must be reconstructed independently of wisdom, since wisdom is also something computers can never achieve. Is it possible such reconstructions will create feedback loops that erode our perspective on our own needs, values, and responsibilities? After all the money and effort poured into making machine intelligence mimic organic intelligence, might we find we have inadvertently created a world where human intelligence mimics the machine?

After all the money and effort poured into making machine intelligence mimic organic intelligence, might we find we have inadvertently created a world where human intelligence mimics the machine?

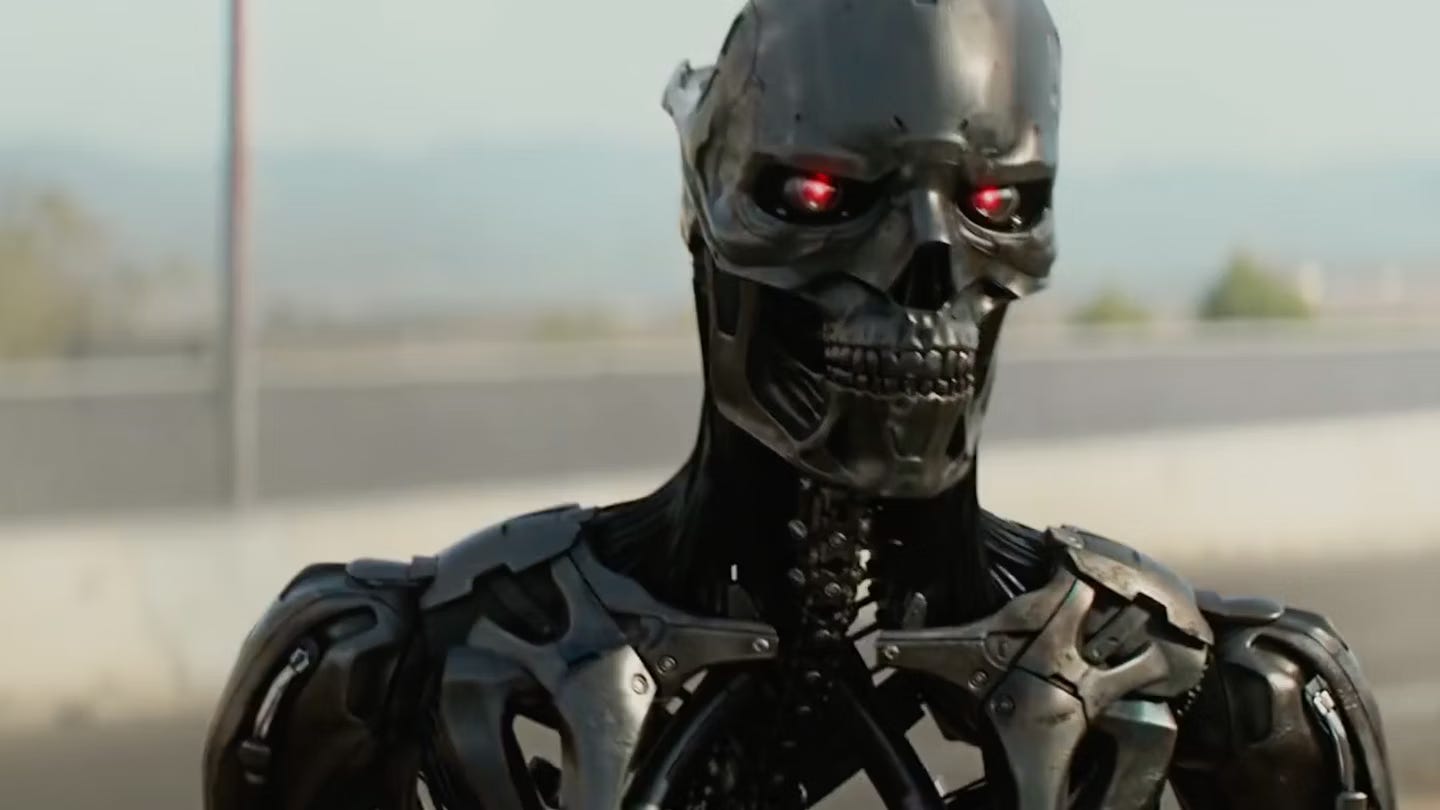

There is already some evidence that we are accelerating into a data-centric world where human thought, imagination, and insight are treated as mere surplus input, even liabilities that must be overcome. That is worse than a killer robot because we don't have a mental map for that kind of a threat.

Here I am echoing warning raised by Matthew Crawford in a 2023 First Things lecture.

In Crawford’s talk, titled “Antihumanism and the Post-Political Condition,” he suggested that antihumanism manifests itself is in the idea that humans are merely inferior versions of computers.” In an environment increasingly customized for computers, humans become the weak link in the system since they are not adapted to the type of clean inputs that automated systems require. He points to what happened when one of Google’s self-driving cars found itself at a four-way stop. Naturally, being a robot, the vehicle was unable to communicate with the other drivers. All the factors that go into negotiating a four-way stop—eye contact, social intelligence, slight movements of the car that indicate a willingness to go, etc.— were invisible to the self-driving vehicle. Not knowing what to do, the car froze and broke down. But the most telling part of this incident is what happened afterwards. When the engineer in charge of the vehicle was asked if he had learned anything from the incident, he said humans need to stop being so idiotic. Crawford invites us to think about the implications in such a statement. When the engineer said humans need to become less idiotic, he meant they need to behave more like computers or, as Crawford put it, “more legible to systems of control and better adaptive to the need of the system for clean inputs.” In short, the human animal must be nudged towards compliance with the machine so as not to disrupt the type of inputs required by automated systems. In My Fair Lady, Professor Higgins famously declared, “Why can't a woman be more like a man?” In the world of digital totalitarianism, the question becomes, “Why can’t a human be more like a computer?”

If these misanthropic assumptions become sedimented in our institutions and way of life, this would clearly represent a threat to human flourishing, yet it is a threat not easily recognized. If a killer robot walked into a city and began turning humans into paperclips, we have a mental map for how to think about that kind of problem. Yet we are less prepared for diffuse and non-attributable system changes that, over time, may subtly problematize uniquely human forms of intelligence, virtue, and wisdom.

If a killer robot walked into a city and began turning humans into paperclips, we have a mental map for how to think about that kind of problem. Yet we are less prepared for diffuse and non-attributable system changes that, over time, may subtly problematize uniquely human forms of intelligence, virtue, and wisdom.

Looking back on my early experiences with ChatGPT, I see that my brain had begun to mimic the machine, as I became trapped in a methodical loop of inputs and outputs. Yet even in the worst throes of the addiction, I knew there was more to my intelligence than mere processing. But what if, as a society, we stop knowing that? Indeed, as we begin reconceiving intelligence in terms of mere processing, does human cognition also become little more than a pragmatic instrument for getting things done? Once intelligence is instrumentalized like this, does it essentially become performative and thus replaceable? In the end, might humans be considered just a type of not-very-effective computer?

The answers to these questions are not fixed. The negative outcomes of AI are not inevitable nor irreversible. It is possible to have a world where AI keeps in its proper sphere, contributing to areas of life where it genuinely has something valuable to offer. But given the stated intentions, goals, and agendas of those involved in developing the most widespread systems currently being used and marketed, I am not optimistic. To tweak the bot’s take on Chesterton, the real danger of artificial intelligence is not that our machines will become more intelligent than we are, but that we will become as unintelligent as our machines.

This article is based largely on chapter 2 in the book I co-authored with Joshua Pauling, Are We All Cyborgs Now?: Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine

REFERENCES

[1] To put it in more detail, using the definition from OECD.AI, “An AI system is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.” “What Is AI? Can You Make a Clear Distinction between AI and Non-AI Systems?” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://oecd.ai/en/wonk/definition.

[2] Matt G. Southern, “Google Says AI Generated Content Is Against Guidelines,” Search Engine Journal, April 7, 2022, https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-says-ai-generated-content-is-against-guidelines/444916/.

[3] In February 2023, technology writer Charley Johnson compiled a range of examples from mainstream media sources, revealing a widespread mystical discourse surrounding ChatGPT and similar bots. Charley Johnson, “The Illusion of ChatGPT,” Untangled with Charley Johnson, February 26, 2023, https://untangled.substack.com/p/the-illusion-of-chatgpt.

[4] Melissa Heikkilä, “How to Spot AI-Generated Text,” MIT Technology Review, December 19, 2022, https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/12/19/1065596/how-to-spot-ai-generated-text/.

[5] David B. Auerbach, “ChatGPT Does Not Hallucinate,” Auerstack, June 2, 2023, https://auerstack.substack.com/p/chatgpt-does-not-hallucinate.

[6] “Computational Theory of Mind,” in Wikipedia, August 13, 2023,

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Computational_theory_of_mind&oldid=1170124549.

[7] Yuval Noah Harari, “The Rise of the Useless Class,” Ideas.Ted.Com , February 24, 2017, https://ideas.ted.com/the-rise-of-the-useless-class/.

[8] Ilya Sutskever, “It May Be That Today’s Large Neural Networks Are Slightly Conscious,” Tweet, Twitter, February 9, 2022,

https://twitter.com/ilyasut/status/1491554478243258368.

[9] Susan Schneider, “Will AI Become Conscious? A Conversation with Susan Schneider,” Princeton University Press, November 4, 2019, https://press.princeton.edu/ideas/will-ai-become-conscious-a-conversation-with-susan-schneider.

[10] Richard Dawkins, cited in “Why Richard Dawkins Thinks AI May Replace Us,” Mind Matters, May 22, 2020, https://mindmatters.ai/2020/05/why-richard-dawkins-thinks-ai-may-replace-us/.

[11] Josh Schrei, “AI in the Age of Mythic Powers by Josh Schrei,” The Bigger Picture, March 14, 2024, https://beiner.substack.com/p/ai-in-the-age-of-mythic-powers-by.

[12] Patrick Butlin et al., “Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Science of Consciousness” (arXiv, August 22, 2023), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.08708.

[15] David Bentley Hart, “Reality Minus,” The New Atlantis, February 4, 2022, https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/reality-minus.

[16] J. Douglas Johnson, “Idol Thinking by J. Douglas Johnson,” Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, December 2023, https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=36-06-003-e&readcode=10988.

[17] For more on how clock technology has impacted human culture and thinking, see Daniel Boorstin, The Discoverers (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1985), 4-78; and Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1934), 12-17.

[18] Norman Doidge shared a number of experiments showing that our tools introduce changes in the circuitry of the brain—changes that often correlate with new ways of viewing the world itself. Norman Doidge, The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science (New York, NY: Viking, 2007).

[19] Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992); Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).

[20] Christian thinkers have long taught that prudence, one of the four cardinal virtues, involves collecting information prior to making a decision. Sometimes information-collecting comes from a human source (e.g. wise counsel or a book), sometimes it comes from a natural source (e.g. evidence of past high watermarks on a river bank), and sometimes it also comes from an electronic source (e.g. a calculator or spreadsheet). There is no reason, in principle, why AI might not fall into the latter category by offering an additional source to inform wise decision-making.

[21] Byung-Chul Han, Non-Things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld (Medford, MA: Polity, 2022), 43.

[22] Celeste Kidd and Abeba Birhane, “How AI Can Distort Human Beliefs,” Science 380, no. 6651 (June 23, 2023): 1222–23, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi0248; “Humans Absorb Bias from AI--And Keep It after They Stop Using the Algorithm,” Scientific American, October 22, 2023, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/humans-absorb-bias-from-ai-and-keep-it-after-they-stop-using-the-algorithm/.

[23] Evidence for an affirmative answer to this last question is already emerging from studies of computer programmers. A December 2023 study published at Cornell University found that “participants who had access to an AI assistant wrote significantly less secure code than those without access to an assistant,” while being “more likely to believe they wrote secure code.” Neil Perry et al., “Do Users Write More Insecure Code with AI Assistants?,” in Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2023, 2785–99, https://doi.org/10.1145/3576915.3623157.

[24] Emma Roth, “OpenAI Introduces Sora, Its Text-to-Video AI Model,” The Verge, February 15, 2024, https://www.theverge.com/2024/2/15/24074151/openai-sora-text-to-video-ai.

[25] Mike Kaput, “‘Jobs Are Definitely Going to Go Away, Full Stop’ Says OpenAI’s Sam Altman,” August 1, 2023, https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/blog/sam-altman-atlantic.

[26] Roman V. Yampolskiy, “Could an Artificial Intelligence Be Considered a Person under the Law?” PBS, October 7, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/could-an-artificial-intelligence-be-considered-a-person-under-the-law.

[27] Nilay Patel, “The Ezra Klein Show: Transcript of ‘Will A.I. Break the Internet? Or Save It?” The New York Times, April 5, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/05/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-nilay-patel.html.

[28] Gary Wolf, “The Data-Driven Life,” The New York Times, April 28, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html.

[29] Robin Phillips, “OpenAI Seeks Mathematical Definition of Goodness,” Robin Mark Phillips, January 1, 2023, https://robinmarkphillips.com/mathematical-definition-goodness/.

I’ve been thinking about this topic and I enjoyed this essay. It seems to me that the best protection against this is strong human relationships. But since human relationships are messy or have friction as you put it, it’s understandable why many might prefer their ai “friends.”

I like that you quoted Charles Taylor. I had him as a professor.