UPDATE: the seminar on beauty referenced below is now available online at Orthodox West Music.

I want to invite my readers to an online seminar this Sunday evening, October 27, on the role of beauty in worship.

For this event I will be joined by Fr. Patrick Cardine and the Orthodox composer, Nazo Zakkak, to discuss why beauty is important in worship. If you are interested in listening, be sure to sign up to get a zoom link sent to you.

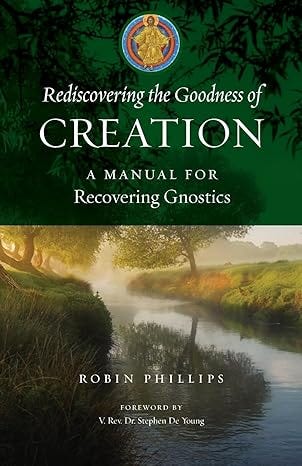

Why am I participating in this panel, and why do I feel strongly about beauty? Part of the answer has to do with something I mentioned in my book Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation. In chapter 15 I observed that our spiritually impoverished world has left men and women hungry for beauty:

Caught in the pincer grip of materialism and the machine, modern humans are hungry for the sublime and the symbolic. Yet in the economy of purpose, where all value is tied to use, there can be nothing sublime nor symbolic, only efficiency or inefficiency in serving a function. The attempt to address this poverty by externally adding aesthetic qualities to the world (for example, Robert Venturi’s decorated sheds, spiritual places in airports, or mindfulness rooms in modern office complexes) is the ultimate parody of the sacramental vision, since it involves the jarring bifurcation of form and content and the conceit that we can layer spiritual-aesthetic nourishment on top of a world already disenchanted and de-symbolized.

This poverty offers Christians an incredible opportunity, yet the modern church has often sacrificed beauty on the altar of pragmatism, Gnosticism, and atheism. Again from Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation:

God has bestowed on some Christians incredible artistic gifts in music, theater, painting, film, poetry, craft, ballet, sculpture, fashion design, literature, and so forth. Yet often, artistic Christians confess to feeling out of place in the Church, especially in communities that offer them no clear sense of how their vocation as artists relates to their vocation as Christians. If an evangelical Christian feels a vocation to be a missionary, a complex body of thought and tradition will help navigate his or her self-understanding; by contrast, there is comparatively little support and understanding for evangelicals whom God has called to pursue the arts, whether full time or as a hobby. Part of the problem may have to do with implicit Gnosticism, together with a Gnostic-like inability to take seriously the doctrines of creation, Incarnation, Resurrection, and eschatology.

Church communities without a strong understanding of creation often view art as purely functional, perhaps as an adjunct to preaching, as a marketing tool, or as a medium for illustrating truths… At best, these approaches leave us with very bad art; at worst, they help fortify the illusion that even the most creative and beautiful artifacts remain spiritually neutral until Christian propositional content or utility functions can be externally imposed.

The theological consequences of these moves are severe, for they concede ground to three great idols of our age: Gnosticism, pragmatism, and atheism. They concede to Gnosticism that the visible world of space, time, bodies, and stuff is not important to God. They concede to pragmatism that the value of an artwork lies in functional goals outside the work itself. And they concede to atheism that works of aesthetic creativity are in themselves spiritually passive and neutral—a realm independent from the Creator God. Those committed to theism may revolt against the idea of any discipline as autonomous from God, yet they may try to redeem art through extrinsic means rather than returning to a theology that shows all that is good, true, and beautiful as already Christian by its very nature.

The first step toward a recovery of beauty is, of course, bringing beauty into worship. Christians can talk about the importance of beauty all day long, and even advocate a coherent theology of beauty, but this will mean little if worship itself does not reflect the beauty of transcendent holiness. Yet unfortunately, many Christian churches I’ve visited are practically indistinguishable from warehouses, while much contemporary worship music is simply bad pop music with religious lyrics. This creates a dangerous vacuum that is being filled by the counterfeit transcendence of UFOs, psychedelics, or even the incomplete beauty of a romanticism that would merely stop at transient beauty without following it through to the Source.

If beauty is important, then we need to start in the house of God, and that means recovering beauty in worship. So please join us on Sunday evening as we discuss this important topic. Again, to get a Zoom link, register here.

Further Reading