Welcome to “The Epimethean,” your guide to defying the machine through embodied living.

Many of you already know me from my website www.robinmarkphillips.com and from my books. I started this Substack to open up a new front for my writing ministry focused more explicitly around the virtues of embodiment and to foreground a figure from Greek mythology who can be our guide.

We’re likely all familiar with the story of Prometheus, the Titan who famously stole fire from the gods. Through his act of rebellion, Prometheus bequeathed to mankind the ability to make iron, and thus all the technological arts. In his inventiveness, indomitable ambition, and rebellion against limits, Prometheus represents the spirit of technological man in the modern age. Not without reason did Karl Marx refer to Prometheus as “the most eminent saint and martyr in the philosophical calendar.”

But if Prometheus was the god of communists who would glorify the quest to master nature through industry and the romanticization of the factory worker, he is equally the god of techno-capitalism. Today, as the logic of techno-capitalism leads us to strive to achieve emancipation from creaturely limits, what better patron saint than the rebel Prometheus? As we work to create forms of artificial general intelligence that will surpass—and perhaps even supplant—the human, what better hero than the one who stole the primordial fire from Athena and Hephaestus to empower the human race?

But the Promethean vision comes at a heavy cost. In Deschooling Society, the philosopher Ivan Illich (1926 –2002) warned that Prometheus’ heirs are not simply content to use fire to forge iron; rather,

contemporary man attempts to create the world in his image, to build a totally manmade environment, and then discovers that he can do so only on the condition of constantly remaking man to fit it. We now must face the fact that man himself is at stake.

As an antidote, Illich draws attention to Prometheus’s less-known younger brother, Epimetheus. History has not been kind to Epimetheus, who is remembered as one lacking foresight. When the Titan brothers were tasked with giving gifts to all the creatures, Prometheus provided man with the stolen fire, but Epimetheus found he had run out of gifts, having distributed everything first to the animals.

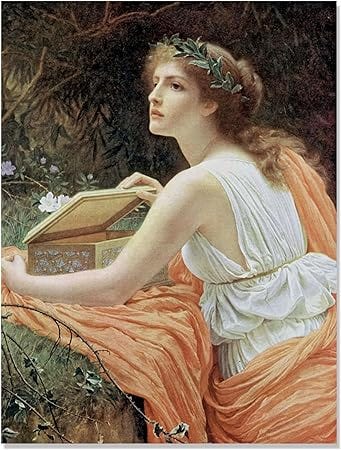

As retribution for stealing fire, Zeus gave humanity the woman Pandora, along with her famed box of evils. Pandora is an Eve figure most known for letting open “Pandora’s box.” Yet, like Eve, she is also the harbinger of hope, the one thing that did not escape from the box.

The story comes full circle when Epimetheus accepts the gift of Pandora from the gods, marrying her against the counsel his elder brother Prometheus.

In the story of Epimetheus, Illich sees the answer to our technocratic obsessions. While Prometheus strove to master what belonged to the gods, Epimetheus embraced the creaturely finitude of humanity by marrying Pandora. Illich sees their union as an act of hope and love, of grace and rootedness. As Joshua Pauling explains in our forthcoming book We’re All Cyborgs Now: Technology and the Christian Faith (Basilian Media, 2024), if Prometheus’s goal was to achieve mastery via the fiery forge, Epimetheus’s was a life of conviviality and humane scale, putting arts and crafts to the service of a uniquely human type of flourishing. Pauling echoes the observations of Richard Kahn who noted that

For Illich, Epimetheus was not the dull-witted brother of Prometheus-the-savior but rather the ancient cultural archetype of those who freely give and recognize gifts, care for and treasure life (especially during times of catastrophe), and attend to the conservation of seeds of hope in the world for future others.

Prometheus was bound to the consequences of his deed, chained to a rock from which he cannot escape torment. In the hands of the playwright Aeschylus, Prometheus anticipates Milton’s Satan locked in adamantine chains for defying the Almighty.

Our era is undoubtedly Promethean. Lacking any substantive vision of the Good, those at the helm of today’s technocratic order seek more than merely the secrets of using fire to make iron: they seek to make and remake human nature at will in order that, liberated from the constraints of nature, mankind may become truly free. As Marc Andreessen exclaimed in his much-discussed techno-optimist manifesto last year,

We believe technology is liberatory. Liberatory of human potential. Liberatory of the human soul, the human spirit. Expanding what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive… We believe in nature, but we also believe in overcoming nature.

Under the hubris of this techno-optimism—which comes at the heavy cost of a digital totalitarianism that technologizes all of life—there is nothing given that is not finally contingent. Even the limitations of our own biology—for example, our givenness as men and women—become just a bit of provisional epiphenomena waiting to be overcome by the technological imperative of continual progress without limits. Indeed, in the era of digital totalitarianism, the limitation of embodiment represents a kind of fall from which digitality promises redemption. Yet as I argued in an essay last year for The Symbolic World, progress without a substantive vision of The Good must ultimately fold into nihilism, revealing this emancipatory enterprise to be not freeing but enslaving.

In seeking emancipation from the limits of embodied life—with all its vulnerability and normativity, its fragility and beauty—are we in danger of losing all that makes human life beautiful in the first place? Are we, like Prometheus, inadvertently forging chains that will bind us to the consequences of our actions?

If Prometheus is the patron saint of our technocratic era, his brother Epimetheus represents the embrace of creaturely limits. While Epimetheus is remembered as the one lacking foresight (even his name means “afterthought”) it is actually Prometheus who lacked foresight. While Prometheus was chained to the consequences of his deed, his brother Epimetheus went on to experience the joys of domesticity with his human bride, and thus to build a distinctly human culture.

The one is the path of the cyborg and involves embracing the cultural order that Paul Kingsnorth and others have referred to as “The Machine.” The other is the path of the human and involves embracing both the limitations and beauty of life on a humane scale.

This publication is a place where we rage against the machine. But it is also a place where we celebrate all those things that make us distinctly human: art, music, literature, craft, cooking, hiking, and leisure (understood in the classical sense). This will be a place where we foreground the stories of ordinary men and women who have found hope and liberation, not through the Promethean impulse to overcome nature at all costs, but through embracing the traits, practices, and virtues that enable us to flourish as humans. We will interview everyone from digital minimalists to hobbyists to craftsmen to artists to musicians to educators who, in the spirit of Epimetheus, have found hope in a distinctly human way of life. We will also profile men and women working in the tech industry who are producing humane and creative products that advance more traditional visions of human flourishing.

Above all, the Epimethean community will be a place where we rejoice in the limitations God has given us, and find ways to live, not as cyborgs, but as embodied creatures, connected to God and each other.

Welcome!