An expanded version of this essay has now been published as the last chapter in Are We All Cyborgs Now?: Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine, by Robin Phillips and Joshua Pauling.

Computer engineer, Anthony Levandowski, is famous for being the co-founder of Google’s self-driving car program. What is less well-known about the tech guru is that, in 2015, he established a non-profit religious organization, “Way of the Future.” The purpose of this non-profit was to create a god using AI.

Wired Magazine journalist, Mark Harris, got hold of documents from the organization when writing a 2017 piece on Levandowski. These papers express the group’s intention to “develop and promote the realization of a Godhead based on Artificial Intelligence.” In a follow-up piece, Harris expanded on the content of these documents.

The documents state that WOTF’s activities will focus on “the realization, acceptance, and worship of a Godhead based on Artificial Intelligence (AI)developed through computer hardware and software.” That includes funding research to help create the divine AI itself. The religion will seek to build working relationships with AI industry leaders and create a membership through community outreach, initially targeting AI professionals and “laypersons who are interested in the worship of a Godhead based on AI.” The filings also say that the church “plans to conduct workshops and educational programs throughout the San Francisco/Bay Area beginning this year.”

Harris sat down with Levandowski and asked him if the emergence of an AI god is the same thing that some people refer to as the “singularity.”

Levandowski prefers a softer word: the Transition. “Humans are in charge of the planet because we are smarter than other animals and are able to build tools and apply rules,” he tells me. “In the future, if something is much, much smarter, there’s going to be a transition as to who is actually in charge. What we want is the peaceful, serene transition of control of the planet from humans to whatever. And to ensure that the ‘whatever’ knows who helped it get along.”

With the internet as its nervous system, the world’s connected cell phones and sensors as its sense organs, and data centers as its brain, the ‘whatever’ will hear everything, see everything, and be everywhere at all times. The only rational word to describe that ‘whatever’, thinks Levandowski, is ‘god’—and the only way to influence a deity is through prayer and worship....

Enter Way of the Future. The church’s role is to smooth the inevitable ascension of our machine deity, both technologically and culturally. In its bylaws, WOTF states that it will undertake programs of research, including the study of how machines perceive their environment and exhibit cognitive functions such as learning and problem solving.

Speaking on the “Flash Forward” podcast, Mark Harris exulted that “this is the first god you will be able to literally talk to and get a response from,” adding that “its aims are to develop, realize, and worship a godhead in artificial intelligence - developed through computer hardware and software. It’s basically to build a God, to build a god from the ground up."

“Its aims are to develop, realize, and worship a godhead in artificial intelligence..to build a God, to build a god from the ground up."

Though “Way of the Future” was dissolved in 2021, the basic idea of using AI to create a god, to connect with beings in the spirit realm, or to transition into a new level of spirituality, has only picked up momentum. Later in this essay I will share some more of the quasi-spirituality that has developed around AI. But first, some personal background about how I became interested in this topic.

Is AI Demonic?

I first became interested in the spiritual implications of AI when Paul Kingsnorth suggested that AI is demonic. I’ve always been a fan of Paul Kingsnorth’s “Abbey of Misrule,” but when he published a feature in Touchstone on why AI is demonic, it was a bit much for me. I interacted with Paul’s views on my author website here and here and here, in addition to corresponding with him about it. My position was clear: AI is not demonic.

Yet now I am forced to admit that Paul may have been onto something.

So why have I changed my mind?

It began when I took a deep dive into the Ancient Near East (ANE) to explore the context for scripture’s teaching on the early origins of technology. There is no easy way to explain this without offering quite a lot of historical background. If ancient history isn’t your thing, you can pick up the conversation about AI in the section below titled “Toward a Modern-Day Tower of Babel.”

Why Ancient Near East?

In the Bible, the first reference to someone building something comes in Genesis 1:1 when God made the heavens and the earth. This is the beginning of a theology of technology, yet the import is easily missed because we do not share the thought world of the Ancient Near East (ANE), the original context for Genesis. To an ancient reader or listener, the account of God creating the Garden of Eden would have been understood as a temple construction narrative. The clues are everywhere in the text once we understand something about temples in the ANE.

In the mindset of the ANE, the purpose of religion was not for humans to go to heaven, but to bring heaven to earth. But what was heaven? Heaven was a place in the sky where a nation’s god was believed to be enthroned above the gods of rival nations. The goal of politics and “religion” (this is before the two had bifurcated) was for the pattern of the cosmos to be realized in earthly society– in short, for each nation to rule over rival nations even as their god ruled in the heavens over the gods of the other nations. The way to achieve this “as in heaven, so on earth” dynamic was through a temple-city complex.

Once enthroned in his temple, a nation’s god could take command, ultimately through the prophetic leadership of the god-king with whom he was associated. The god-king would serve the roles of prophet, king, and priest to connect earth with heaven. The prophetic function occurred via the king’s access to the deity enabling him to receive divine will, leading to inspired law and order. (Justice not derived from the gods was seen as illegitimate, which is why as late as Roman times, an emperor derived legitimacy through claiming to be the son of a god.). The prophet-king duality occurred as the ruler established his supremacy on the earth over rival nations through military adventurism. And the priestly function occurred as the prophet-king connected heaven and earth through his own person, believed to be sponsored by the god or even a substantiation of, or a descendent from, the deity. As king-prophet-priest, the god-king (in the words of Dr. John Walton) “stood between the divine and human realms mediating the power of the deity in his city and enjoyed their favor and protection.”

When a nation built a temple, the construction process would culminate in an initiation ceremony placing the god’s image inside, thus enabling the god to descend from heaven to dwell within that image while still continuing to live and reign in the heavens. (Some temples, such as Ziggurats, actually contained stairways for the god to use when descending to the earth.) During this initiation ceremony, the mouth and nose of the god’s image would be opened, allowing the god to come and inhabit it. The image was then believed to manifest and embody divine presence, thus establishing the temple as sacred space. The god’s presence in the temple, in turn, established it as sacred space, making possible the dominion and expansion of his favored nation. To be successful in this expansion, however, the people believed they needed to meet the needs of their god via worship and sacrifice, often including human sacrifice.

Sacred space was thought to diminish the further one moved outward from the temple. But the idea was always to extend sacred space through more temples and images. As the god’s people expanded, they placed his image throughout their territory. Or else they placed images of their god-king who, as we have seen, was particularly associated with the deity. The geographical and numerical expansion of the images served an important political function in marking out their territory, and thus serving a function similar to a nation’s flag today. For the most powerful rulers, such as the pharaohs of Egypt or the emperors of Babylon, the images they constructed extended over thousands of miles. Part of the colonial impulse involved defacing or destroying rival images.

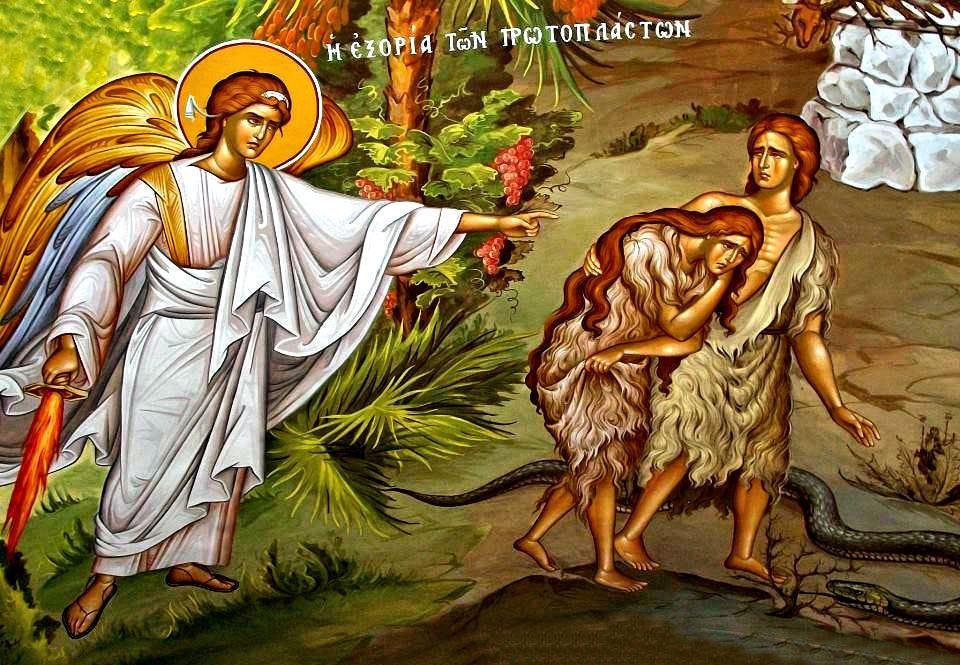

Technology Before the Fall

Genesis, a literary product of the ANE, would have been understood against this larger cultural backdrop by its original hearers. I agree with Dr. John Walton and Fr. Stephen De Young that, to the original audience, the days of creation would likely have been taken as a temple construction narrative. God was building the sacred space of Eden to fill with His presence. And in keeping with ANE symbolism, the crowning moment of this ceremony came when God placed His image in the temple and then breathed into his nostrils the breath of life so man could become a living being. But unlike in pagan temples, it is God who opens the nostrils of man and breathes life into him, so he can function as His image. Instead of man building a temple and then bringing a god built by human hands to inhabit it, God Himself builds a temple (Eden) and then puts His image (humankind) into it; rather than man opening the nose of his god’s image to activate divine presence, the true God opens the nose of his image (man), to bring his presence into the temple (Eden).

The command to be fruitful and multiply can also be more fully appreciated against this ANE backdrop. Remember that in the ANE, the god’s rulership in his temple was mediated outward via the leadership of the nation’s king, who established sovereignty through the numerical and geographical expansion of his god’s image. The true God was also concerned with the geographical and numerical expansion of His images (mankind), as seen in his command to multiply and fill the earth (Gen 1:28). Remember that in the ANE, holiness diminishes as you move further away from the sacred space of the temple. Eden was sacred space, but it did not fill the entire world; rather, God tasked his images with the vocation of subduing the earth in His name, thus making the rest of the earth Edenic and habitable for divine presence.

In short, mankind was meant to make the entire earth heavenly—to marry earth with heaven. Whereas ANE man saw stone images as the means for linking heaven and earth, God gave men and women the vocation of uniting heaven and earth. To fulfill this vocation, men and women were to be fruitful, to subdue the wilderness outside the garden, and to shepherd the earth with loving husbandry. All this would extend the sacred space of Paradise as a continuation of God’s creative activity when He spoke life into the void. Rather than a single god-king being tasked with connecting earth and heaven, mankind was given the vocation to be mediator between the visible and invisible, the material and the spiritual, and ultimately to serve as priests between God and the rest of creation. This vocation is reflected in man's dual nature: the rational, spiritual, and heavenly united with the sensible, bodily, and earthly. As the link between the earthly and the heavenly, mankind is tasked with the dominion mandate: raising the beasts upward (for example, through loving stewardship to enable animals to achieve their telos) and bringing heaven downward (guarding and tending the earth with loving stewardship so it is habitable for God’s presence).

Part of the task of exercising loving stewardship over creation is to imitate God’s activity. Just as ancient god-kings were believed to reflect and look like the primary image in the temple, which itself reflected the prototype who reigned in heaven, so humans, as images of God, reflect and imitate God. For example, God creates life (Gen 1:1), and so do we; God speaks (1:3), and so do we; God exercises aesthetic appreciation (1:31), and so do we. Most relevant to the present discussion, God makes things, and so do we. Following Tolkien, we can use the term “sub-creation” to refer to our participation in God’s creative activity as we make things of our own out of the raw materials provided by the primary Creator. But the imperative of sub-creation goes beyond mere imitative activity; rather, it is part of how we fulfill our vocation to exercise loving husbandry of the earth. Whereas ANE kings believed they reflected glory back to their god by building temples and conquering other nations, mankind reflects glory back to the true God by making things within the context of loving stewardship of earth’s resources. In short, the garden was meant to be worked. As John Dyer explains,

God designed the garden—even before the fall, sin, and death—in such a way that it needed to be worked on. It's not that there was anything wrong with the garden; it's just that God didn't intend for it to stay the way that it was. Instead, God wanted Adam to ‘cultivate’ or ‘till’ or ‘work’ what he found in the garden and make something new out of it....God created the garden not as an end point, but as a starting place. Adam's job was to take the raw materials of the earth—from the wood of the trees, to the rocks on the ground, to the metal buried deep within the earth—and create new things from them. In a sense, Adam was to take the ‘natural’ world—what God made—and fashion it into something else—something not entirely 'natural' but sanctioned by God.

If uninterrupted by sin, the vocation to subdue and develop the earth would no doubt have culminated in culture, which is why Genesis 1:26-28 and 2:15 are often referred to as the “cultural mandate.” Adam and Eve were given a world rich in cultural, technological, aesthetic, and institutional potential: a world where the resources could be used to make musical instruments, paintings, opera houses, institutions, and entire societies. This is part of how mankind extends the sacred space of Eden outward and thus connects heaven and earth: not through military adventurism like ANE god-kings, but through lovingly developing the earth’s resources to reflect glory back to the prototype in whose image we were made. This would have occurred qualitatively (extending sacred space through more of the earth until the Garden of Eden covered the entire globe) and qualitatively (discovering and using more of earth’s resources). This qualitative aspect points toward technology.

The technological potential latent in the earth’s resources included,

Technologies that extend man’s strength. Examples would be anything from a lever to a forklift, from an axe to a chainsaw, from a shovel to a bulldozer.

Technologies that extend man’s intellectual capabilities. Examples would be anything from an abacus to a graphing calculator, from a notebook to a database, from written language to a computer.

Technologies that extend man’s aesthetic potential. Examples would be anything from a musical instrument to a paintbrush, and any tool that enables us to create beauty and art in its various forms and media.

Technologies that restore man’s health or mitigate impact of death. Or Examples would be anything from eyeglasses to LASIK surgery, from essential oils to vaccinations, from crutches to a prosthetic leg.

Notice that only the fourth type of technology presupposes the fall. The world given to Adam and Eve was without sin, but it was not perfectly mature and developed. If the innocent condition had continued, Adam and Eve would no doubt have served as king and queen over a thriving civilization rich in technological inventiveness and creativity. Of course, we know this did not happen.

Technology After the Fall

After Adam and Eve sinned, they were banished from God’s presence and cast out of Eden. Yet the technological imperative was not revoked at the fall. Mankind continued to be responsible for exercising loving dominion over the earth and its resources. In the covenant with Noah, God reiterated the doctrine of the imago dei (Gen 9:6), along with a recapitulation of the obligations given to Adam and Eve (Gen 9:1-7). Yet in the postlapsarian condition, man’s working of the earth, like woman’s birth-giving, is a hardship because the natural world no longer cooperates with man’s monarchy. The disorder goes both ways: just as the earth now rebels against man’s rulership, man also rebels against the earth, abandoning loving husbandry for exploitive control.

In the reign of death, the fourth use of technology becomes necessary, namely technologies that work to mitigate the impact of our fallenness. The first example of this type of technology is actually something God Himself made: the garments of skin to clothe and protect Adam and Eve once they became aware of their nakedness (Gen. 3:21). These required the death of an animal, indicating man’s new relationship to the earth’s resources. The garments of skin are essentially a healing technology, filling in for something that had been damaged at the fall.

Man’s relationship to the earth was also damaged since he can no longer use the world’s resources from a position of access to God’s presence. After the fall, God placed cherubim with a flaming sword at the east of Eden to guard the way back to the sacred space where man had once enjoyed intimate communion with Him. The absence from God’s presence has significant implications for the evolution of technology in the line of Adam’s son Cain.

Given that the technological imperative continued in the postlapsarian condition as an outworking of the cultural mandate, it is perhaps surprising to find that when Genesis describes the production of technology, it comes from the line of Cain, a murderer whose family is tainted with sin.

After Cain killed his brother, he was condemned to wander the earth. This wandering starts with him leaving the presence of the Lord (4:16), a second and further iteration of the exile of Adam and Eve. Even in Genesis 4, after their expulsion from Eden, God’s presence had not been completely lost, for the text records God talking directly with Adam’s family. But Cain and his descendants are involved in a series of successive exiles that further solidify the loss of God’s presence. Even the curse on the ground given to Adam in Genesis 3:17 is intensified with Cain (Gen 4:12). Prevented by God from working the ground and thus staying in one place, Cain is condemned to the status of a hunter gatherer. Yet God committed to defend him and put a mark on his forehead as a promise of protection (4:15).

What does Cain do? He builds the first city (4:17), and begets descendants that have livestock (4:20), develop musical technologies (4:21) and work with bronze and iron (4:22). One might see these technologies as simply an outworking of the dominion mandate given to Adam and Eve, and indeed I have argued that myself elsewhere. Yet the text does not present this first contact with technology as an unqualified good. Though Cain has the status of a fugitive wanderer, God had promised to protect him. Yet instead of trusting God’s protection, he turned to technology for help, first by building a city – a rebellion against his wandering status. Through the city, Cain seeks glory for himself. He names it after his son Enoch (4:17), part of the attempt of man to “make a name for ourselves,” (Gen 11:4) which would later culminate in the hubris of Babel.

But the settled life of the city is more than just an ego trip for Cain’s family, and it is more than merely a rejection of his wandering status. The city is Cain’s attempt to use technology to supplement the powers lost at Eden, to achieve the marriage of heaven and earth through hubris. This can be missed by modern readers because we do not typically associate cities with technology now that the entire developed world has the characteristics of a city. But we need to note a few things about ancient cities.

Cities and Nation States in the ANE

In the early stages of human urbanization, common people did not live in cities. Rather, the city was a temple complex, with public structures like granaries and administrative buildings attached to it. As cities later expanded to include common dwellings, the temple remained the heart of the city. As we have seen in our earlier discussion of ANE religion, at the heart of the temple was an idol, which established the temple as sacred space. We also saw that these temples often had towers and stairs next to them to facilitate the descent of the god—a kind of executive elevator for the fallen angel (believed to be a deity) to descend from heaven and receive worship. In short, the earliest cities in the ANE were demonic.

Another important feature of ancient cities is that they required the type of division of labor that is only possible within environments of surplus food production. That is why large cities tended to be limited to regions with large domesticable mammals, as Dr. Jared Diamond has shown. When everyone is involved in hunting, gathering, or subsistence farming, there can be no specialists to build city structures, or to serve the administrative roles those structures facilitate. Specialists in a city would include a permanent priest caste to offer continual sacrifices to the gods, but as the city increased in power, more specialists could be added. For example, bureaucrats could be hired to organize the public treasuries, and to use the surplus resources to finance engineers, scholars, artisans, metallurgists—in short, to support all the technological arts.

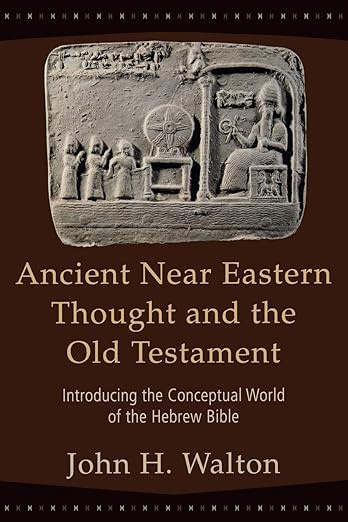

In ancient cities, the technological arts included more than what we normally label as “technology,” for they also encompassed magic. As Dr. John Walton explained in Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament, in the ANE there was no clear demarcation between technology and magic since both were mechanistic techniques, understood as a type of “science.” Indeed, for people in the ancient world, the technological enterprise was spiritual, because there was no realm of “the spiritual” detached from the rest of life. We see this even in how early physicians—the witch doctor or medicine man—was an expert both in medical “technologies” like herbology, as well as the ways of the spirit realm. The city-temple complex facilitated technology in this broad sense, and was seen to provide special potency for harnessing secrets for becoming powerful. In Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, the connection between cities and secret power was particularly strong. Cities were believed to be products of the gods, to have existed before humans, and to mediate the seen and unseen realms. Cities thus became central in man’s primordial quest to connect heaven and earth, yet not through repentance, but through mechanism and hubris.

Cities thus became central in man’s primordial quest to connect heaven and earth, yet not through repentance, but through mechanism and hubris.

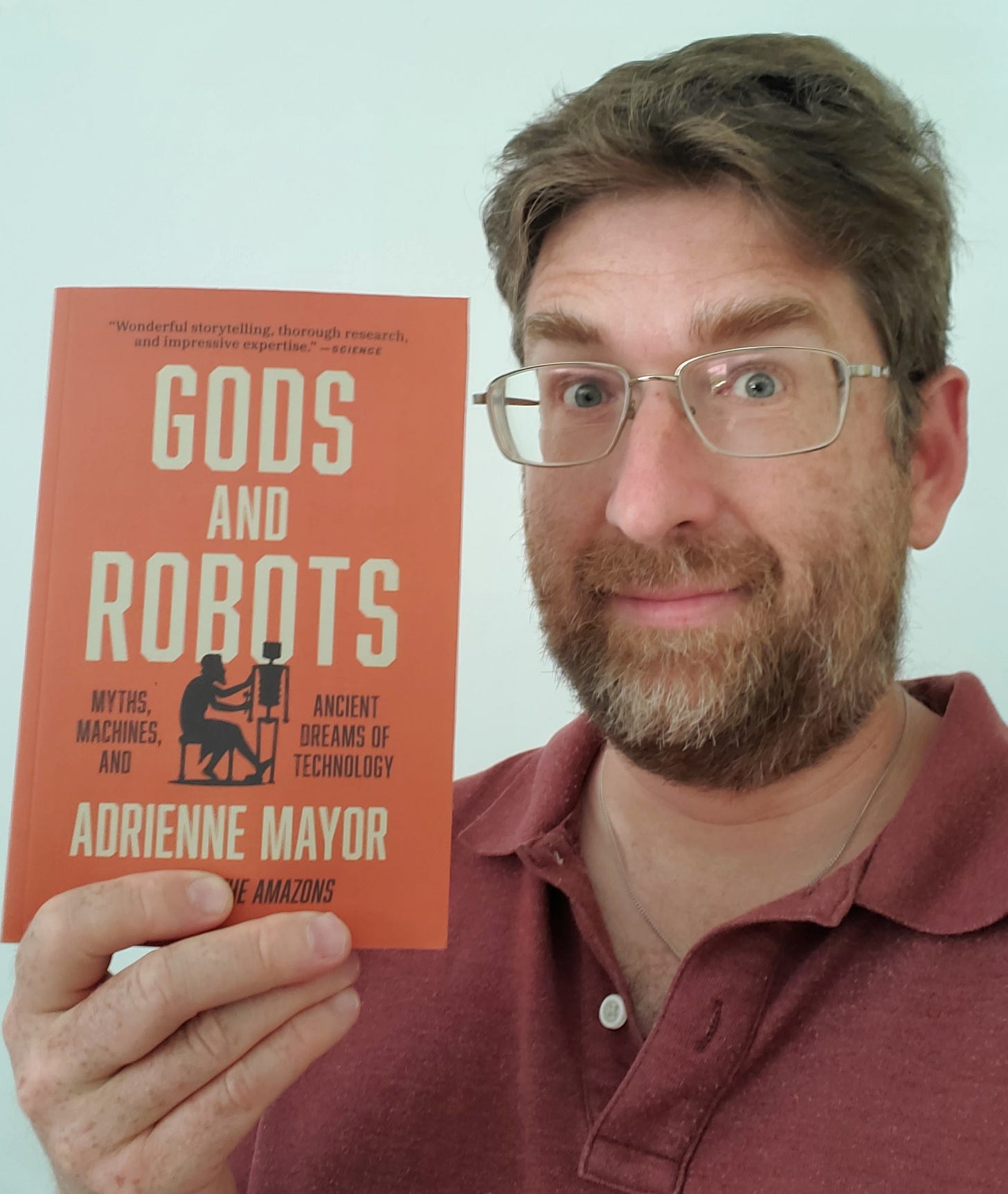

Significantly, some of the earliest automation technologies were invented for purposes of idolatry, with automatons used in temples to impress the faithful. In Adrienne Mayor’s Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology, she documented how a Buddhist monastery in India had “many automaton guardians in human and animal forms” that were likely animated by primitive mechanics. Some temple technologies enabled obscuration of the human voice in order for priests to channel messages from the gods. For example, an ancient statue of the Egyptian sun god Ra-Harmakhis was found with “a cavity in the back of the neck from which a narrow canal leads to an opening on the right jaw under the ear.” The purpose of this cavity was likely to enable a priest to speak into the tube, which would modify his voice in order to convince the faithful that Ra was delivering oracles.

In some temples, mechanical devices may have actually been animated by malevolent spirits. In AI Narratives: A History of Imaginative Thinking about Intelligent Machines, there is a fascinating chapter by Minsoo Kang and Ben Hallibutron. They recount how “the divine prophet Hermes Trismegistus describes how the ancients used astrology to entice supernatural beings into artificial images to speak prophecy, cure the ill, and bring fortune to the good while punishing the evil.” Other legends abound from the ancient world about using a severed or mechanical head being used for oracular purposes.

But beyond using technology as a mechanism for idolatry, city technologies made possible the nation state, and thus the empire. A ruler could use the city’s resources to finance a standing army, expand his territory, capture slaves, and hire officers to enforce centralized decision making. This enabled nations to amass wealth and power not possible in earlier forms of social organization, whether bands, tribes, or even large chiefdoms. Ultimately this resulted in a glorification of violence, such as what we read about in Homer. (In the Iliad, for example, violence allowed men to achieve a type of immortality through their memory in song, while in the Odyssey, Odysseus is praised for acts of piracy and is even given the title “sacker of cities” as an epithet of praise.)

The sacred space at the heart of the city remained the control room for this violence and the justification behind it. That justification, we recall, is that the nation’s god ruled in the heavens above the gods of the other nations, a cosmic reality that was incapsulated in the microcosm of the temple. Consequently, in conquering, enslaving, and butchering one’s enemies, ANE soldiers believed they were simply imitating the activity of their god. And in some sense, they were correct: no doubt the fallen angels clamoring for worship and power had no loyalty to rival leaders in Satan’s kingdom.

Besides the problem of violence, nation states created new problems not known to humans in smaller units of social organization. One problem, which we don’t even perceive as a difficulty because we have developed various work-arounds, is the problem of interacting with strangers. In the most primitive forms of human organization, humans dwelt in bands or tribes small enough for everyone to know everyone else. But when human community transitions into a nation state, the question becomes how to achieve cohesion among groups of unfamiliar people? How does a state convince a mass of strangers to get on board with the laws and commandments? Contrary to what many people think, this cohesion is not achieved through the threat of punishment, because not even the most powerful modern police force could operate without broad consent from most citizens. Nation states use a variety of mechanisms to convince citizens of legitimacy, from origin stories to national ideologies to conditions of perpetual emergency (hence the importance of war, threat of war, or “permanent revolution”). But in the ancient world, the primary mechanism to convince people of legitimacy was a ruler’s claim to be divine or descended from the god, or at least to be sponsored by the deity. As a state expanded to include peoples who do not share a common ethnic and cultural background, the less the ruler can rely on organic bonds to keep the people together, and the more necessary it becomes for him to convince the population that he is divine, and that his laws proceed from a divine source – which is to say, that the justice he brings reflects the type of larger cosmic order represented by the city-temple complex.

Again from Dr. John Walton’s book Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament:

For the kings of the ancient Near East, the highest value was the legitimization of their reign (much in the same way that in American politics the highest value is often reelection). Integrally related to this value was the concept of divine sponsorship, which in its turn was dependent on the king’s demonstration of wisdom. The king demonstrated his wisdom by showing insight in judgments and, in general, by the way in which he administered justice…. So it is that the king, with the sponsorship and endowment of wisdom from the deity, administers justice.

Even in a chiefdom, the largest form of social organization next to the nation state, it would be impossible for everyone to know each other as in bands or tribes. “Hence,” writes Jared Diamond in The World Until Yesterday, “chiefdoms develop shared ideologies and political and religious identities often derived from the supposedly divine status of the chief.”

But a ruler’s claim to divinity was not the only way to organize people in large groups. Earlier I mentioned that surplus food production enabled a city to have specialists, among them bureaucrats. In the ancient world no less than today, when people are grouped into structures too large to be self-organizing according to the organic logic of relationships (roughly, groups larger than 150), bureaucratic procedures become necessary to enforce centralization and top-down measures of social control. That is why the technological orientation that emerged out of ancient cities brought human society, human relationships, and human behavior within the scope of the mechanical mind. It is simply not possible to automate human behavior—whether a standardized workday, resource allocation and extraction, standardized legal codes, etc.—without bureaucratic administration.

How The City and Nation State Became an Anti-Eden

We now have more pieces in place to understand how the aspirations of the ancient city represented an anti-Edenic economy. In Eden, the true God tasked mankind with expanding sacred space outward through lovingly tending the earth; in the city, false gods (fallen angels and god-kings) task man with creating a false sacred space and then expanding it outward through violence and idolatry. In Eden, mankind imaged the Creator God through lovingly tending the earth; in the city, god-kings imaged fallen angels through brutally conquering and enslaving others. The center of Eden was man and woman’s union with God, and this lead to rightly ordered relationships with one another and—had Eden continued uninterrupted—harmonious social communities; the center of the city is union with false gods leading to disordered relationships and disintegration (i.e., people crammed together who do not know one another).

Many of these aspects are already nascent in Cain’s city in Genesis 4. The significance of Cain’s descendants keeping livestock (4:20) is not merely that this occurred before the slaughter of animals was authorized in the covenant with Noah, but that it facilitated the type of surplus food production that is essential to division of labor and therefore development of city technology. While Cain’s descendent Jabel is keeping livestock, Jabel’s brother Jubal is specializing in musical instruments while their half-brother, Tubal-Cain, develops the art of metalwork (4:22). By introducing technology to man, Cain becomes a type of Prometheus figure, discovering the secret arts for manipulating the earth and using technology to supplement the powers lost to man at the fall.

How did Cain learn these secrets? There is some evidence that he may have obtained his information from fallen angels. Consider that, to quote from Fr. Stephen De Young’s book,

Genesis 4-6 parallels—and was perhaps even crafted as a polemical response to—a Mesopotamian kings list in which human rulers are taught by divine beings, known as apkallu, the arts of metallurgy, astrology, and ancient wisdom. Whereas in the Mesopotamian story, this gave the rulers power and legitimacy, Genesis subverts the myth, showing that the pursuit and illicit knowledge leads to death, ultimately the flood.

Fr. Stephen expanded on this in an intriguing blog post, “The Angels Who Left Their Former Estate”:

These chapters of Genesis interact polemically with Mesopotamian religious belief, but they do not themselves preserve the traditions upon which Genesis comments. These traditions were, however, preserved in a multitude of Second Temple Jewish texts, most famously in 1 Enoch, but also in a multitude of other texts such as the Book of Giants from among the Dead Sea Scrolls. These connect the two opposing traditions in a way that makes the original context and interpretation plain. Cain’s descendants produce these cultural and technological innovations because they are receiving these secrets from angelic beings who are giving them over not in order to assist mankind, but in order to aggrandize themselves and be worshipped by humanity and to ultimately destroy humanity by giving over secrets for which humanity are not ready. Their sin is therefore directly parallel to the sin of the Dragon in Genesis 3. They follow after his example. And so it is that God punishes these angelic beings by imprisoning them in the abyss, in the underworld beneath the earth until the last day when they will find their judgment in the lake of fire (cf. 1 Enoch 21:6-7).

Further evidence that Cain’s family may have obtained knowledge of technology from fallen angels is found in the Book of Enoch. When this ancient text describes the events that made the deluge necessary, the author recounts how fallen angels gave mechanical secrets to man, including knowledge of “how silver is produced from the dust of the earth, and how bronze is made upon the earth.” They also impart secrets of how to make weapons and cosmetics.

And Azaz’el taught the people (the art of) making swords and knives, and shields, and breastplates; and he showed to their chosen ones bracelets, decorations (shadowing of the eye) with antimony, ornamentation, the beautifying of the eyelids, all kinds of precious stones, and all coloring tinctures and alchemy.

Whether Cain or his descendants actually derived technological knowledge from fallen angels, it is clear that Cain paved the way for the debauchery of the ancient city and the nation states that would follow, all of which come to function as a surrogate Eden. Josephus recognized Cain’s role the emergence of nation states, and points out that he was the first to partition land and create a regularized economy through fixed measures and weights. Here is what Josephus writes in his Antiquities of the Jews:

He augmented his household substance with much wealth, by rapine and violence: he excited his acquaintance to procure pleasure and spoils by robbery: and became a great leader of men into wicked courses. He also introduced a change in that way of simplicity wherein men lived before; and was the author of measures and weights. And whereas they lived innocently and generously while they knew nothing of such arts, he changed the world into cunning craftiness. He first of all set boundaries about lands.

Setting boundaries about lands is Cain’s ultimate rejection of his wandering status, reaching for the power of the nation state. As that power requires weapons, it is significant that Cain’s descendent, Tubal-Cain, begins making things with bronze and iron (Gen 4:22), a likely reference to early production of swords and spears. Notice also that Josephus describes Cain teaching wickedness, a probable reference to Cain being master of the dark arts, through which he attempted to forge the lost connection with heavenly powers. In short, Cain’s city, situated “east of Eden” (4:16), is his attempt to create a new world. This is even reflected in the name he chose for his son, Enoch, which means “initiation” or “dedication,” in Hebrew. Cain’s city, named after Enoch, stands as an antitype to Eden. This is a point observed by the late Fr. Matthew Baker in one of the last sermons before his tragic death. This is a point observed by the late Fr. Matthew Baker in one of the last sermons before his tragic death.

This is the anti-Eden: an economy, a social order, all of man’s making. Cast out from God’s kingdom, Cain founds his own kingdom – a kingdom without God. With Cain’s descendants, Jabal, Jubal, and Tubal-cain, come the marks of civilization: agriculture, fine art, technology (Gen. 4:20-22). But, as the story of Lamech shows, these benefits are accompanied by a continued pattern of vengeance and bloodshed (Gen. 4:23-24). This story indicates for us the deep moral and spiritual ambiguity—to say the least—which surrounds the city and all that it represents. All human communities, even those with the greatest achievements of human culture, are disfigured by sin. There is no civilization in the history of the world that has not in some way been built and maintained by a flight from God, by idolatry and brutality, the exploitation and killing of other human beings. This pattern is confirmed by the two cities mentioned next in the book of Genesis: Babel (Gen. 11) and Sodom (Gen. 13-14; 19).

Fr. Matthew mentions Babel, which marks a turning point in primordial man’s relationship to technology. But Before discussing Babel, it will be helpful to pause and reflect on the state of mankind at this point. The basic picture that is emerging is one we are all familiar with, living in a cursed world. After the fall it became harder to believe in God’s protection and to live in the reality of our total dependence on the Creator. With man’s lost powers over the world, with the ground rebelling against his monarchy, with the constant threat of natural disaster, technology offers an attractive supplement. By making things, by uncovering the laws that govern the universe, by harnessing the resources of the earth, it becomes possible to begin manipulating the world mechanistically, and thus fortifying the illusion that we are not dependent on God. But this comes at a terrible cost. Technology only burrows us deeper into the separation from God and alienation from the world and each other that occurred when our first parents were driven out of Eden. As Jacques Ellul observed in The Meaning of the City,

Cain, with everything he does, digs a little deeper the abyss between himself and God. There was a solution for his situation, but the solution was in God’s hands, and that is what he could absolutely not tolerate. He wants to find alone the remedy for a situation he created, but which he cannot himself repair because it is a situation dependent on God’s grace. And Cain accumulates remedies, each one a new disobedience, each one a new offense. Each remedy which seems to be a response to a need in Cain’s situation, in fact sinks him even deeper in woe, into a situation ever more inextricable… He forces creation to follow his destiny, his destiny of slavery and sin, and his revolt to escape from it. From this taking possession, from this revolution, the city is born.

Cain’s rejection of his wandering status, and his desire to make a name for himself through the glory of a city in his family’s honor, sets humankind on a trajectory that eventually culminates in intercourse with spirit beings and the Nephilim of Genesis 6. Other traditions from the time, such as the Babylonian Apkallū myth already referenced, describe human kings paired with godlike beings that offer technological secrets, including metallurgy and astrology. (For more about this, I recommend the Lord of Spirits podcast, and their episode, “The Art and Science of Technomancy”). Genesis itself describes mankind coming to have great power, as represented by “giants” and “mighty men who were of old, men of renown” (Genesis 6:4). God responded to this state of affairs by sending the great flood and starting over with Noah’s family. Yet this did not solve the basic problem, as occult practices after the flood had striking similarity with those before. Did one of Noah’s sons or daughters-in-law take books of esoteric secrets into the ark? While we cannot know the answer to this question for sure, the Sibylline Oracles describes Noah’s daughter-in-law Sambethe becoming a prophetic priestess (read: witch) in Babylon.

Whether Sambethe transmitted demonic secrets to the postdiluvian world, or whether the wickedness came through other means, it is clear that the human race quickly fell back into the very same temptations, particularly the temptation to build cities that became centers of ungodly power. This is described in The Book of Jubilees, an ancient expansion of Genesis popular in Jesus’ day and cited by New Testament authors. Jubilees lists the various sins mankind succumbed to and includes that they began “to build strong cities, and walls, and towers” and “to found the beginnings of kingdoms.”

The Tower of Babel and Technological Hazards

Ancient man retained the impulse to mediate earth and heaven, but this mapped onto false worship. Man retained awareness of his priestly status, but instead of linking earth with heaven in an ever-widening doxology of praise to the true God, man connected to fallen angels, inviting them down into his temples. Man continued longing for the sacred space lost at Eden where he enjoyed intimacy with the Creator, yet he tried to create sacred space through intimacy with false deities and the idolatry of god-kings. Through the arts of magic, false worship, and technology, mankind tried to control and manipulate these deities to underscore his own prideful agenda, take dominion of the earth in hubris, and use various mechanical means to supplement the powers lost at the fall. All of this culminated in the hubris of Babel.

In Genesis 11:4 we read that the people of Southern Mesopotamia said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top is in the heavens; let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad over the face of the whole earth.” Here the mechanical impulse, represented by the city-temple-tower complex, is directly connected to the primordial vocation of connecting heaven and earth. The language of “a tower whose top is in the heavens” can be found throughout Mesopotamian literature to describe ziggurat towers. Here is a picture of the ruins of the Ziggurat of Ur.

These temple-towers were based on the idea that mankind could meet the needs of gods. By meeting the needs of gods (chiefly their need to receive worship and sacrifice, but also their need to have a sanctuary to rest in), people believed they could manipulate the god to help them achieve power, rule over other peoples, prevent disintegration (recall Cain built the first city as a rejection of his wandering status), achieve greatness – in short, to make a name for themselves. Babel is thus the culmination of the attempt to recover sacred space, to create an anti-Eden. Dr. John Walton outlines this very clearly in a brief talk given at Wheaton College.

It was not just the demonic sacred space of the ziggurat that was an anti-Eden. The technological enterprise itself, so central to the temple-city complex, moves mankind further from his image-bearing vocation, making it easier to favor domination over husbandry, power over stewardship, control over cultivation. Moreover, human societies built on top of mechanistic infrastructures introduce new risks and hazards that further burrowed mankind into the reign of death through new hazards. We can illustrate this with some examples from our own time. A hazard associated with the hammer is that it enables you to construct buildings quickly, with the result that you might be in such a hurry that you don’t pay attention to the type of building you’re creating. A hazard associated with boots is that now you can walk more easily in the dark, so you might be over-confident venturing into the woods at night. A hazard of electric light is that it allows one to escape from the natural cycles of day and night to reach for greater productivity or entertainment even while becoming further separated from natural circadian rhythms. A hazard associated with cooking technology is that, while we can more easily leverage plants for food, we are tempted to eat things that we were never meant to consume and which, in a pre-mechanical era, would have been impossible to harvest (e.g. vegetable oils).

At the political level, a hazard of both war-making mechanisms and bureaucratic techniques is that it becomes possible to organize human beings—often unwillingly, through the threat of violence—into social structures larger than God originally intended men and women to live within. The leader/s of a city will exert control of the surrounding countryside; the city will become a nation state; the nation state will turn into an empire, where a few people have unprecedented power over thousands of other men and women. Something like this seems to be happening with both Cain’s family and Babel. The city gave man confidence to reject the wandering status ordained by God; instead of spreading out over the earth, man stayed in one place to accumulate power. Rather than using technology in ways that are restorative like the garments of skin, man uses mechanical arts—concentrated in the ungodly city—to enhance human power beyond what is safe and wise.

In Genesis 11:6, after surveying the centralization of power at Babel, the Lord declared that “now nothing that they propose to do will be withheld from them.” The underlying idea — as Richard Rohlin explains in his conversations about Babel here and here — is of a people growing in power so that nothing, and no one, will escape them. This is even more evident in the Jubilees tradition, where the narrative describes a growing power that threatens to draw everything and everyone the orbit of its domination. Seen in this context, the single language is emblematic of a totalizing system, an oppressive unity. And, of course, God broke up the Babel project by confusing their languages and “scattering them abroad over the face of all the earth” (Gen. 11:9).

If we simply read Genesis 1-11 and no further, it would be easy to conclude that cities, temples, and nation states are unqualifiedly bad, or that God desired for mankind to remain always in a paleolithic condition. But just as the Church Fathers suggest that God eventually intended for Adam and Eve to eat from the Tree of Life, the Lord also intended for our dominion of the earth to culminate in cities, including their technology. Yet as we will see in the ensuing story of Israel, mankind had to reach a stage of maturity before cities could be built, and part of that maturity is God-dependence.

Technology and the Covenant with Abraham

How do we know that the Lord intended for our dominion of the earth to culminate in cities and associated technology? Well, notice what happens right after the story of Babel in Genesis 11. In Genesis 12 we read about the call of Abraham — a call which, through the course of redemption history, culminates in the city of God, Jerusalem. If one looks closely at Genesis 11 and 12, it appears that Abraham was called out of Babel, the city of man, to build its antitype, the city of God. As Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick explains,

Abraham's story, which you can read starting at the end of Genesis 11, immediately follows the Babel story, so the impression one gets is that God calls him out from Babel. The Ur that he left may be identified with the Sumerian city called Uruk, and it notably is the site of a great ziggurat, which you can visit in the modern country of Iraq. The Bible therefore presents a continuum of various names that all encompass one image, whether you want to call it Eridu, Babel, Ur, Uruk, or Babylon. This city is the creation of humans, filled with demonic evil and dominated by fallen angels who teach humans evil. God tasks Abraham, therefore, to leave Babylon and begin a new nation, which will become Israel, called out by God not only from Ur but eventually also from Egypt, which was functioning as Babylon for the Israelites in that period—a city of evil, ruled by demons.[1]

The covenant with Abraham does not result in a city for almost half a millennium. Through various tests and trials, God solidifies Abraham’s family, revealing more and more of Himself to this people. This people largely had a wandering status, living first as foreigners in Egypt, then as slaves, then as desert wanderers. But rather than being allowed to reject their wandering status like Cain and the builders of Babel, the children of Israel were forced to accept the purifying fires of exile before they could move to the next stage of cultural maturity. That maturing process involved learning how to use both technology and city.

While Abraham’s descendants are wandering in the desert, God revealed to Moses numerous laws concerning tools and the process of making things. We find in the Torah detailed instruction concerning everything from garments construction to food preparation to aesthetic technologies. Regarding the latter, we read that God granted Bezalel and Oholiab the skills necessary to make a beautiful tabernacle, “to make artistic designs for work in gold, silver and bronze, to cut and set stones, to work in wood and to engage in all kinds of crafts” (Ex. 31:4-5). But God also provided boundaries on mechanical innovation, as seen in the prohibition against idol construction, laws against unethical forms of warfare, and warning against hazards in Bronze Age agricultural society (for example, over-farming the same land). Ultimately, these laws re-situate technology within the original vocation to tend, guard, and subdue the earth.

The form of these laws is just as important as their content. It is significant that these laws, together with their further expansion in the Wisdom Literature, resists the mechanical mindset by situating justice and law within relationships and situation-specific prudence. Laws are to be interpreted and applied by wise people (judges, prophets, kings) rather than bureaucratic systems and techniques.

At the heart of all the technological teaching in the Torah is instruction for building the city, Jerusalem, where God had promised to dwell. The Jerusalem temple is God’s answer to both Cain’s city and Babel. The builders of Babel wanted to make a structure to connect earth with heaven, invite their god to live in it, and thus make a name for themselves. The true God revealed that He also wanted to build a house to connect heaven and earth (Ex. 26:30), to live in (Ex. 25:8), but for the purposes of making His name great (2 Chron. 6:20; 7:16; 1 Kings 8:43). He reveals that a physical building will act as a restored Eden, and that the context for this will be an actual city, namely Jerusalem. If the city of Babel and its temple-tower was fallen man’s answer to the loss of Paradise, the city of Jerusalem with its temple is God’s answer to Babel.

This is the restoration of Paradise on God’s terms. The temple, replete with Edenic symbolism, is a recapitulation of the sacred space that had been lost in our first parents’ exile. As with the ancient ziggurat, the temple acts like an elevator to connect heaven and earth, and it is even associated with a stairway. Consider, when Abraham’s grandson Jacob had a vision of “the gate of heaven” (Gen. 28:17), it is reminiscent of the gate to Eden that had been barred (Gen. 3:24). But in the former case, Jacob saw a stairway linking heaven and earth, with angels ascending and descending on it. The site of this vision, and the stone associated with it, becomes emblematic of “God’s house” (Gen. 28:22), in a foretaste of God’s presence in the temple that would later be built. (See my discussion of Jacob’s ladder in “Life, Longing, and Ladders in the Land of Shadows.”)

Thus, we have a progression that we can summarize as follows:

Genesis 1-2: God’s presence established in Eden;

Genesis 3: God’s presence lost through expulsion and death;

Genesis 4-11: Attempt to regain God’s presence through technology, and the city-temple complex;

Genesis 12: Re-establishment of God’s presence through covenant, law, temple, Jerusalem.

We have seen that each of these stages came with a particular type of relationship to technology. In Eden the relationship with technology was situated within the larger cultural mandate, including the imperative to connect heaven and earth as God’s image-bearers. With the loss of God’s presence, however, man came to have a new relationship to the earth, while technology took on a new role in mitigating the impact of the curse. It is not necessarily evil to use technology to alleviate the impact of death, as seen in the fact that God made garments of skin to protect Adam and Eve. Yet after the fall technology innovation enabled an increase in wickedness, as seen in temples to false gods and war-making technologies. These mechanical innovations made possible ANE nation states centered around the worship of false gods. Yet God did not completely eschew the technological enterprise: we saw that through the call of Abraham, He reestablished sacred presence through a covenant that would eventually entail a temple, city, and even nation state. Significantly, God’s covenant involves bringing mankind to a state of maturity in order to use technology within the primordial vocation to lovingly tend and guard the earth. We saw that many of the laws in the Torah point toward a redeemed use of technology that recapitulate man’s primordial vocation to be God’s image-bearers. This redeemed use of technology climaxes in the re-establishment of sacred space in the Jerusalem temple.

The Purified City

Jerusalem was meant to be a type for what a city can be. With the worship of the true God at the center, the city can achieve its proper telos. Rather than facilitating disintegration, the city can promote social harmony. Rather than bringing violence to the surrounding countryside, people in the surrounding lands come to Jerusalem to experience peace and prosperity (Ps. 122; Is. 60). Rather than burrowing man deeper into exile from God, Jerusalem offers redemption. But Jerusalem was not the only city mentioned in the context of redemption. The Israelites were commanded to set aside six cities as places of refuge for foreigners (Num. 35:15). As John Dyer explains, “God was asking his people to use cities in a way that was contrary to their built-in tendencies of use and their sinful inclinations. Instead of using them to keep foreigners out, the Israelites were to use them to invite people in, into life with God and his people.”

Even within the context of the covenant, however, both technology and the city retain an ambiguous status. The stones for the temple are to remain uncut. And the city of Jerusalem, though in some sense typifying salvation and the return of God’s intimate presence, retains echoes of Cain’s rebellion. Again from Fr. Matthew Baker’s sermon:

Even Jerusalem does not escape this ambiguity. Jerusalem is “comely” (Song of Songs 6:4), but only in the future. The prophets prophesy the great day when Jerusalem shall be holy (Joel 3:17), when God will dwell in her and she will be called “a city of truth” (Zech. 8:3). But in the meantime, she is filled with injustice, having “grievously sinned” (Lam. 1:8). She is called a sister to Sodom (Ez. 16:46-47), even Sodom itself (Is. 1:10; Jer. 23:14; Rev. 1:18), the city “which kills the prophets” (Mt. 23:37).

Amid this ambiguity about Jerusalem are continual hints that it is not God’s final solution. Many of the prophets foretold a time when God’s presence would be diffused throughout the earth, rather than concentrated in the sacred space of the temple. Remember that sacred space diminished the further one moved outward from the temple. This is one of the reasons that faithful Jews took pilgrimages to Jerusalem, while the unfaithful were threatened with removal far away from Jerusalem, a sign of being cut off from God’s presence. But the prophets foretold that one day sacred space would no longer be concentrated in the temple. Ezekiel saw a vision of a river flowing from the temple, a sign of God’s sacred space filling more of the earth in a recapitulation of the original intention for Eden to spread. This vision was connected to a redemption of technology. For example, Isaiah and Micah described people beating their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks (Is. 2:4 Mc. 4:3), while the eschatological visions of Isaiah were replete with references to technology being used to glorify God in a new Eden or what the prophet calls “new heavens and new earth” (Isaiah 65:17).

Jesus, New Jerusalem, and the Sanctification of Technology

This promise of renewed Eden reached its penultimate fulfillment in Emmanuel (“God with us”) when God tabernacled with men and dwelt among us (John 1:14). This is the culmination of the covenant with Abraham and a restoration of Eden, when God walked and talked with man in the Garden (Gen 3:8). During His earthly ministry, Christ condemned the temple and lamented the loss of God’s presence from Jerusalem even while fulfilling both of these in His own person. By being the true image of God (Col. 1:15), he fulfils the Edenic vocation. His life-giving death brings us into the true sacred space that the Jerusalem temple anticipated (Heb 9), while his ascension to the right hand of the Father united human nature to heaven (Eph 1).

Christ promised that, after the ascension, God would take up His dwelling in man permanently through the Holy Spirit, which now dwells inside all the faithful and is present in the church through word and sacrament. The coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost reversed the curse of Babel and was the true reality of which ancient ziggurats were the corruption. God’s presence with His people in the Spirit enables the re-integration of earth and paradise that we experience in the sacramental ministry of the church. This is an advance foretaste of the final climax when the New Jerusalem descends to the earth to make all of the cosmos Edenic (Rev. 21:1–4).

While the promise of New Jerusalem is future, a key theme throughout the New Testament is that now that the earth has received the second person of the Trinity in Emmanuel and the third person of the Trinity at Pentecost, the eschatological future has been inaugurated in the new covenant. Thus the church, as the people of the new covenant, can begin subduing the wilderness and tending the earth as God’s renewed images. And this, of course, involves sanctifying technology.

The sanctification of technology occurs most obviously in the production of the blessed sacraments. As the agricultural mechanisms of any given culture are put to the service of bread-making and the fermentation of wine, these technologies become mystically caught up in the synergy of the sacramental act. Through the Blessed Eucharist, even the technological artifacts of pagans are transformed by the church’s sacramental activity. This, in turn, points to a future time when the technological artifacts of pagans will be transformed by the church’s sacramental activity. If this seems like a shocking statement, consider that in the Isaianic vision of a New Heavens and a New Earth that sets the context for Revelation 21 and 22, the ships of Tarshish (an object of God’s destructive judgment in Scripture – see Is. 23:14; Ps. 48:7.) become the very means by which the wealth of the pagans is brought into Jerusalem (Is. 60:9). While the new Jerusalem will certainly be a restatement of Eden, it will also be a purified recapitulation of human culture and creativity. “The new Jerusalem,” as Andy Crouch reminds us, “will be truly a city: a place suffused with culture, a place where culture has reached its full flourishing. It will be the place where God’s instruction to the first human beings is fulfilled, where all the latent potentialities of the world will be discovered and released by creative, cultivating people.” Fr. Matthew Baker expands on this concept in his sermon already cited.

And just as in the Exodus into the promised land the people of Israel brought with them the spoils of Egypt (Ex. 3:21-22), the silver and the gold gathered in the land of their affliction, so also into this holy city “the kings of the earth shall bring their glory” (Rev. 21:24): “whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise” (Phil. 4:8)—all things of beauty and genuine creativity which have been made or accomplished within the city of man, shall in some way be found in this new Jerusalem, the city of the living God. The human polis and all that it represents—human history, human culture—is not only judged; it is also cleansed and sanctified, redeemed—if only now “in hope” (Rom. 8:24; cf. 8:25).

“What shall pass from history into eternity?” asked Fr Georges Florovsky, of blessed memory. “The human person with all its relations, such as friendship and love. And in this sense also culture, since a person without a concrete cultural face would be a mere fragment of humanity.”

This purification of human culture—including the sanctification of our technological artifacts—can begin now, this side of the eschaton. Indeed, one of the striking features of New Testament theology is that God’s future has come rushing into the present. As our lives and communities are transformed by the Spirit and ordered around Christ’s presence in the church, God’s inaugurated kingdom can be a reality on earth. That may sound like a charter for utopianism, yet Christian theology recognizes that the “already” of Christ’s inaugurated kingdom can merely anticipate, in faltering and incomplete ways, the “not yet” of the coming consummation. Like the patriarchs of old, we too anticipate “a better, that is, a heavenly country” (Heb. 11:16) when the earth will be renewed and married to heaven.

This same principle can be understood in spatial terms. We remain in the situation, understood so powerfully in the ANE, where there is a site of sacred space with diminished holiness the further removed one gets from the center. God has returned to earth in the Logos and the Spirit, reestablishing Eden through the renewed temple, namely the church. But as in the ANE, there is diminished holiness the further removed you are from the temple. Thus, the further one gets from the church, the more sacred space diminishes. We observe this at every level: geographically, we see that lands without the church are dark, while families who live far away from a church community often struggle to raise Christian children; culturally, we notice that as a society becomes less informed by the church there is societal breakdown and chaos; personally, we observe that those aspects of our lives not integrated with the church become less coherent and well ordered.

This dialectic between the center and the periphery, or between the already and the not-yet, gives us a context for a qualified affirmation and skepticism of the cultural products (including technology) wrought in the present age. This is important, because in current debates there tend to be Christians on the tech-affirming side and the tech-skeptical side, and often these are framed in oppositional terms. But the beauty of the redemptive-historical framework is that it enables us to unite these within the broader dialectic between the already and the not-yet, the center and the periphery. Let’s explore how this sheds light on a practical issues regarding technology, before circling back round to the question of AI.

Technology Between Incarnation and New Jerusalem

Using the redemptive-historical framework outlined in this essay, we are justified in adopting an affirmative posture toward the role technology can play in mitigating the impact of death. We recall that the first postlapsarian instance of someone making things was God making garments of skin for our first parents. In a small measure, this compensated for the impact of death, with the resulting vulnerability to cold, shame, lust, etc. We still live under the reign of sin and death, but just as Christ fought against death through healing people, we can use technology to fight death and its impact. While the church certainly fights against spiritual death through evangelism and discipleship, the church also acts as an agent of renewal through supporting technology and inventions that help advance—in particular and incomplete ways—Christ’s ongoing victory over death. For example, many missionary saints worked as doctors or set up hospitals to care for the sick, leveraging technology in the arts of healing and pain relief. Other saints wrote about health: for example, in my book Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation, I have an entire section about St. John Chrysostom’s teaching on self-care, and how he advocated various medicinal remedies to help with ailments. Christians today can continue in this tradition by embracing the potential new technologies have for good. If these technologies are pursued in a Christ-honoring way, then even this side of the eschaton, they need not burrow us deeper into alienation from God but can approximate something of Christ’s healing ministry.

Jesus never presented his miracles of healing as a complete solution to the world’s problems, or else He would not have needed to endure the costly sacrifice of the cross. Similarly, neither should we look to our machines and technological know-how as a cure-all for everything wrong. As John Dyer reminds us, “We can and should use technology to ease suffering and aid in human flourishing, while also remembering that technology does not have the power to offer complete salvation and restoration. God alone will do that, and it will be quite costly for him.”

This side of the eschaton, there will be constant tension between the sanctifying vs. dehumanizing approaches to technology. And here the Church has an important prophetic role to play in warning against dehumanizing trends. Today, no less than in the ANE, sinful man uses his tools to force creation to follow him in slavery and sin. We see this all around us as we progressive poison the planet and create unsustainable ecosystems. As Christians living in the fulfilled covenant with Abraham, our prophetic vocation can be grounded in the technological principles given to our forefathers. While it is true that we are no longer bound by Torah, the fundamental technological principles in the Old Testament remain vitally relevant. In today’s context, those principles involve asking questions like: how do we use technology humanely in a world where information is valued more than communion, process more than substance, efficiency more than flourishing, the tree of knowledge over the tree of life? Are there tools so powerful that, as a species, we are simply not yet ready to wield, even as humanity was not ready for the city during the time of Cain?

When mechanistic innovation is used sinfully, the church can exercise her prophetic vocation in speaking out, just as John the Baptist spoke out against Herod. But more than merely offering critique against this or that wrong use of technology, the church has the opportunity to show—through our liturgy, our sacraments, our communities, and our way of life—what it means to renew the human in a mechanical age, even as the children of Israel were meant to be an example to the godless nations of the ANE. For example, if we reach a condition where most of the world is chatting to bots and giving lonely people robot companions, the church can offer an outlet for real human connection. Moreover, at a time when there is much fear and anxiety about emerging technologies, the Church can offer solace with the doctrine of God’s sovereignty.

Part of this prophetic vocation is modeling what it looks like to be wise inhabitants of the mechanical age. We may not think of ourselves as living in a mechanical age, as the word “mechanical” tends to evoke systems with moving parts. Our world may not feel as mechanical as the days of pneumatic tube systems in office buildings, or giant clocks you could crawl inside. Our technologies have parts that move at the electrical level, largely out of sight unless you happen to live near one of Google’s giant data centers. Yet in a sense our society represents the triumph of mechanism, since the technological turn of mind now encompasses even thought and emotion. Every time I go into the local Barnes & Noble, I am struck by how everything from wellness to anti-aging to wealth accumulation to finding happiness has been reduced to a technique. The subtext is that suffering is only a mistake for those who haven’t discovered the right mechanism. This is the same worldview as Cain and Babel: through the right techniques, we can insulate ourselves from the effects of the fall. As with every lie, however, it is based on a grain of truth. In a mechanical age, we certainly are partially mitigated from the impact of death and pain in significant ways. I’m sure none of us would like to return to primitive dentistry or medieval medicine. The problem arises when we fall into the sin of Cain’s family by using technology to obscure our total dependence on God. In a technological society, we may not feel the need to ask God to send the rain, to keep wild animals at bay, to provide food. Yet through asceticism, prayer, and spiritual disciplines, we can retrain ourselves to the reality of our total God-dependence. In this way, we can strive to be wise inhabitants of technological society beyond specific responsible uses of individual tools.

Part of wisely inhabiting a mechanical age is to be aware of how today, no less than in the Ancient Near East, our machines continue to be at the forefront to establish an anti-Eden, and to re-establish contact with heaven in pride. And that brings us back to AI and the concerns that Paul Kingsnorth has been raising.

Toward a Modern-Day Tower of Babel

We have seen that the early origins of technology in the Ancient Near East involved seeking to leverage technology for surrogate salvation, transcendence, and sacred space. Consider how the quest to use technology to connect heaven and earth, and thus achieve an anti-Eden through false worship is as potent today as it was for Cain and the architects at Babel. We see this most prominently in the utopian hopes attached to AGI, as well as in new forms of mysticism and pseudo transcendence correlative with machine culture.

The transhumanist movement is a potent example of the primordial quest to marry heaven and earth with a type of surrogate sacramentality. Here is how Meghan O'Gieblyn, one-time transhumanist, describes the spiritual longings that animate this moment. From her article, “God in the Machine,”

What makes the transhumanist movement so seductive is that it promises to restore, through science, the transcendent hopes that science itself has obliterated. Transhumanists do not believe in the existence of a soul, but they are not strict materialists, either. Kurzweil claims he is a “patternist”, characterising consciousness as the result of biological processes, “a pattern of matter and energy that persists over time”. These patterns, which contain what we tend to think of as our identity, are currently running on physical hardware – the body – that will one day give out. But they can, at least in theory, be transferred onto supercomputers, robotic surrogates or human clones. A pattern, transhumanists would insist, is not the same as a soul. But it’s not difficult to see how it satisfies the same longing. At the very least, a pattern suggests that there is some essential core of our being that will survive and perhaps transcend the inevitable degradation of flesh.

A universe without a designer is a scary place, for it ushers us into a world that is meaningless and dumb. Yet as O'Gieblyn observes, we create new gods to fill the void, and these offer the promise of a new sacred space. Within this new space of quasi-spirituality, we begin to realize the dream of Lewis’s Screwtape, who wanted a world in which the materialist magician was no longer an anachronism.

The hope to use technology as a portal to transcendence is not limited to the transhumanist community. In 2006, Fred Turner published the monograph, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, showing that some of the earlier innovators of cyberculture saw the internet as offering the same type of transcendent aspirations as the 60’s counter-culture, with its hopes of the transformative power of back to the land utopianism and flower power. For technological utopians centered in the Bay Area, “cyberspace offered what LSD, Christian mysticism, cybernetics, and countercultural ‘energy’ theory had all promised: transpersonal communion.” What digital technology had in common with the acid trip was a new sacred space centered on “a shared dream of disembodiment.” While those at the forefront of cybercultural innovation are no longer part of the counter-culture, having become part of the corporate mainstream, the initial hope of transcendence through machinery has only grown more potent.

Recall that in the ANE, the sacred space of the temple was a type of control room through which the god spoke his will to mankind. Similarly today, as technology is invested with a sacral significance, we find people using various technologies, and especially AI, to magically connect with spiritual powers in a high-tech Tower of Babel. But what do I mean by “magic”?

How AI “Magic” is Becoming the New Delphi Oracle

When researching this topic, I consulted a scholar with expertise in the cultural history of magic, who asked to remain anonymous. He explained to me that the medieval technical definition of “occult” is “that whose causes are unknown,” while “magic” was understood as the art of dealing with unknown causes. Generally, medieval people divided magic into the following four genera:

Natural magic, where one deals with marvelous and hidden properties of nature (i.e., magnetism or gemstones), and the hidden processes and procedures (i.e., alchemy or astrology).

Prestidigitation or “sleight of hand,” or what we today call stage magic.

Automata / robots. (Yes medieval people did have robots, as evidenced from the famous story of the mechanical head constructed by Albertus Magnus. But as already noted, the first records of automata are from pagan temples.)

Spiritual, angelic or demonic magic, where one manipulates spirits and intelligences.

The first and third were parts of philosophia naturalis (what later becomes natural science). The fourth, of course, was forbidden, but in practice the boundary between these was porous, as seen in the trope of the witch who is both learned in the secret properties of plants and spirits.

The important point is that throughout the Middle Ages, magicians did exist. They were usually part of a clerical/academic underground (at this time, of course, academics were clergy). Priests and other clergy who had trouble getting secure ecclesiastical positions could earn money by performing magic for ambitious courtiers and others who wanted an edge up on their competition. Magic also existed at the margins of academia proper. Priest-professors specializing in philosophia naturalis would be learned about natural magic (and even know about demonic magic, even though the good ones would not touch it.)

What is curious about AI is that it integrates all four of the medieval senses of magic. Clearly AI involves harnessing the hidden properties of the world (i.e., electrical energy), just as it involves discovering the hidden processes of nature (i.e., the processes we’ve discovered for turning rocks into thinking things, that is, to turn quartz into the high-purity single-crystal silicon wafers used in microprocessors). AI also involves quite a bit of sleight of hand, as systems like ChatGPT perform various illusions, leading to a growing anthropomorphizing of bots. And, of course, AI offers the modern equivalent of ancient automata. But what about the fourth sense of magic, where one manipulates spirits and intelligences?

“When we talk about the implications of AI,” said Josh Schrei, “we are talking about powers whose only reference point for us is magical and mythical. Fairyland level powers. Maleficent level powers. Shambhala level powers. Picatrix level powers. Lemegeton level powers. Oberon level powers.” For many, we are not simply talking about these “powers” but talking to them in what amounts to a type of high-tech version of the oracle at Delphi.

D.W. Pasulka, author of Encounters: Experiences with Nonhuman Intelligences reports on the story of a woman called “Simone” who “invests in companies focused on AI, quantum computing, space, and decentralized technologies... She is part of a group of high level AI creators who view AI as an extraterrestrial nonhuman intelligence from beyond space-time.”

Clearly, this is the ancient quest of Babel to create a stairway to heaven for the empowerment of man. If you think I’m exaggerating, listen to Rod Dreher report on AI at last year’s Touchstone conference.

I could multiple examples, but the take-home point is that throughout Silicon Valley, AI is quickly becoming the centerpiece the primordial quest to use technological magic to connect heaven and earth, and to achieve sacred space, not through repentance but through human hubris and pride. In short, AI is becoming a demonic idol along the lines of the Tower of Babel.

Recall that Babel was an attempt to reestablish connection to god/s following alienation from God’s presence after the fall. The attempt to build a godhead through AI is also animated by this sense of loss (recall Mark Harris’s words cited earlier that an AI godhead will be “the first god you will be able to literally talk to,” as if yearning for the Edenic condition when God walked and talked with man). Of course, after the Incarnation and Pentecost, we are able to talk to God directly, and that is what makes this modern-day tower of Babel (“to build a God, to build a god from the ground up") so misguided.

Is There a Ghost in the Machine?

In my earlier dispute with Paul Kingsnorth, I drew a contrast between C.S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength, and the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz.

In The Wizard of Oz, there is no magic, just very clever mechanics. By contrast, in Lewis’s portrayal of a modern-day Tower of Babel in That Hideous Strength, a severed head of a criminal is kept alive, ostensibly through mechanical means, to control and manipulate humans. Yet in the course of the narrative it turns out that the mechanical apparatus thought to control the head is just a front for demonic spirits.