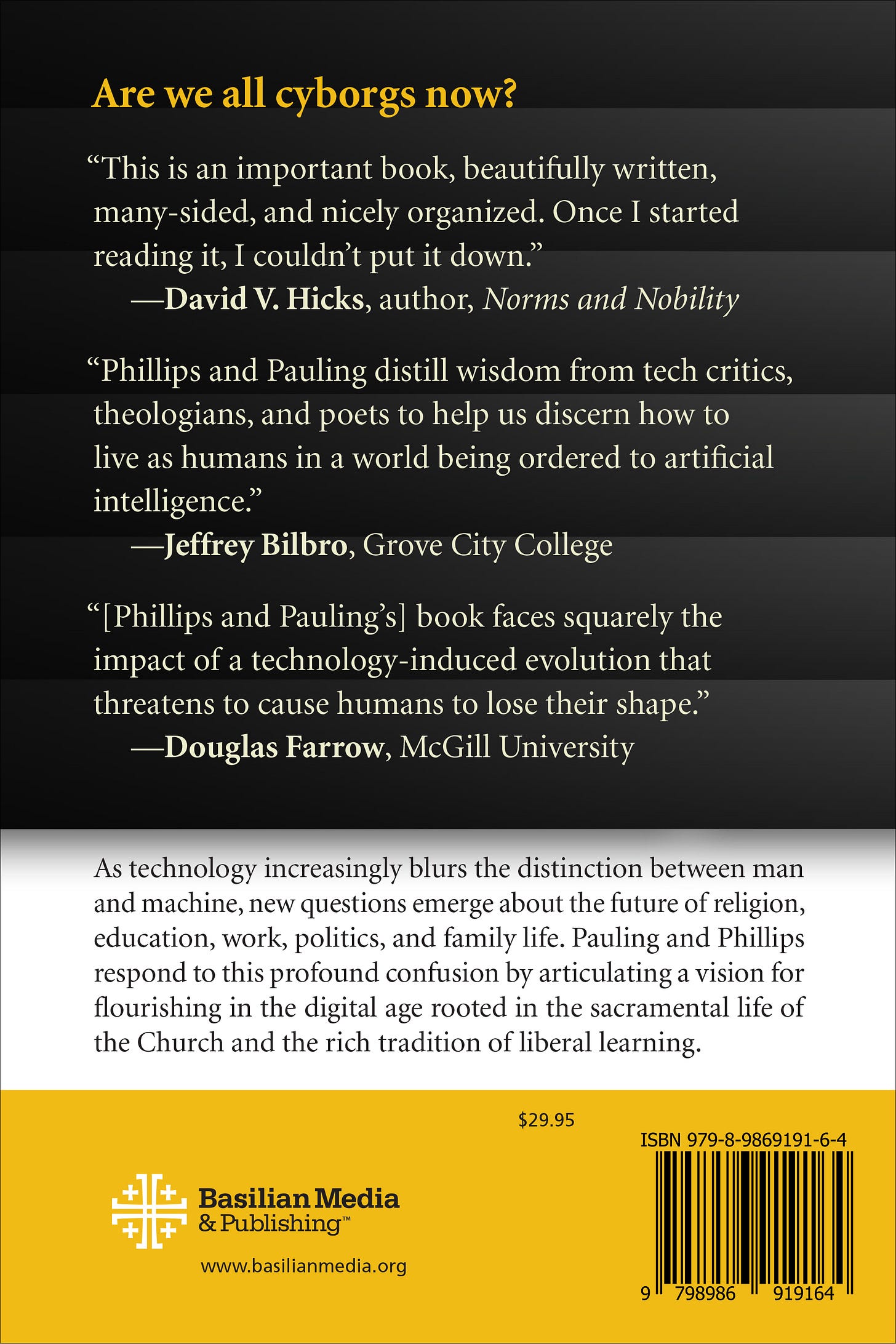

I wanted to let all of you know about my new book, Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming Our Humanity From the Machine. In this book, co-authored with Joshua Pauling, we look at the origins, consequences, and implications of the new technological Prometheanism sweeping the globe. From AI robots to online education to digital girlfriends to an epidemic of technologically-induced ADHD, it is time for a frank discussion of how to reclaim our humanity from the machine. To address these questions, our book offers a toolbox of resources to help families avoid the temptation of Prometheus and recover sensitivity to beauty and appreciation for the slow and quiet things of life.

I’ll share more about Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus later in this article, but first I have some fun facts to share.

Our book, published by the St. Basil Center for Orthodox Thought and Culture, is now on its 10th day as Amazon’s #1 bestseller for new releases in Computers & Technology Education. The book has also risen to the bestseller lists in the following categories:

This is rewarding after all the time Joshua and I poured into the project. We’ve also been encouraged with endorsements from David Hicks, Douglas Farrow, Jeffrey Bilbro, Peter Kwasniewski, Colonel Alex Braszko, and many others. But that isn’t why I recommend you buy and read Are We All Cyborgs Now?

I recommend you get our book because this isn’t just one more narrative stirring up fear about AI, technological addiction, and so forth. To be sure, we do present a lot of scary information, from how smartphones permanently damage the brains of teenagers to what our society and politics will look like once we’ve achieved full AI integration. But the main focus of the narrative is how we can live in a technological age while ordered toward higher goods.

The re-ordering of our affections is two-fold. First, we need boundaries and limits, including ways to block those aspects of technology that are dehumanizing and addicting. But secondly, our hearts need to be stirred by a more beautiful vision than what the techno-utopians of our world can offer.

This two-fold way is represented by the twin stories of Odysseus and Orpheus. Most of us are familiar with the sirens, the birdlike women who lured sailors off course through music so hauntingly beautiful that no mere human could resist the bewitching call. Odysseus navigated around the siren’s isle through boundaries and limits (for example, by ordering his men to block their ears with wax and to tie him to the mast). Odysseus, perhaps aware of his tendency to forget what truly matters and get diverted off course (i.e. remember that his crew reminded him to leave the enchantress Circe and continue the voyage), takes no chances.

For many years I have been inspired by Odysseus’s heroic struggle, as has my co-author Joshua Pauling. But Chesterton Cobb (my Luddite friend whose conversations were influential when writing this book) drew our attention to another Greek hero, Orpheus, who used a very different strategy.

When passing in hearing-distance of the sirens, Orpheus drew his lyre and played music more beautiful. One might say that Orpheus cultivated a positive vision that made the sirens’ song pale into insignificance.

In Are We All Cyborgs Now?, Joshua and I argue that both heroes, Odysseus and Orpheus, can guide us in responding to the challenges of an increasingly technocratic age. Yes, we need properly curated environments and routines that bind us to good habits, just as Odysseus bound himself to the mast. That is why our book offers an entire toolbox of strategies to achieve digital minimalism in the home, and thus resist the siren call of everything from online porn to sexting.

But even more importantly, we need to follow Orpheus in cultivating a more beautiful vision than what our tech-saturated society can offer. Accordingly, our narrative aims to guide readers to rediscover what is truly beautiful about embodied creaturely life so that the bewitching call of digital saturation, techno-utopianism, and digital amusements are seen as ugly by comparison.

When framed and understood within an intentional positive vision, even the forms of self-denial and self-discipline that we practice have a larger purpose, pointing us towards higher goods and ultimate ends. Then even self-imposed limits become a joy and are actually invigorating and liberating.

What is this more positive vision? Ultimately, it comes down to understanding the type of creatures we are and the type of world in which we live—in short, anthropology, cosmology, and metaphysics.

Consider, when God made the world, he spoke meaning into the void of non-being, and he gave form to chaos. When God created men and women, He gave us the vocation of sub-creation, that we too might continue speaking meaning into chaos to make all of the world habitable for divine presence in an ever-unfolding doxology of movement from earth to heaven. Following St. Dionysius the Areopagite and St. Maximus the Confessor, Dr. Timothy Patitsas describes this movement as follows in The Ethics of Beauty:

God was so good that his goodness could not be contained within himself. It poured forth “outside” himself in a cosmic Theophany over against the face of darkness. The appearing of this ultimate Beauty caused non-being to forget itself, to renounce itself, to leave behind its own ‘self’ (non-being), and come to be. All of creation is thus marked by this eros, by this movement of doxology, liturgy, and love. Creation is a movement of repentance out of chaos and into the light of existence.

This primordial pattern at the heart of reality means that to be human is to have an upward yearning to unite with God, the plentitude of all being and the source of true happiness. But this desire to unite with God frequently misfires onto impulses, visions, and schemes that promise heaven but which actually have the status of non-being. These visions include the following axioms of digital utopianism, all of which are now being widely advocated by leading technologists and venture capitalists:

we can build something that will connect us to non-human intelligences;

through this connection we will achieve unprecedented powers, and regain the mastery over nature lost at the fall;

this will essentially lead to utopia – a type of secularized Eden.

These impulses of digital utopianism lure us with counterfeit beauty precisely because they are parasitical on the primordial vocation to unite with God. But this counterfeit beauty—which now has its own pseudo-mysticism, eschatology, and redemption motifs as Silicon Valley takes a quasi-spiritual turn—leads not to life but to death. The result is that sinful passion is being institutionalized within the societal infrastructures currently built around machine-dependence.

Passions have the status of non-being because evil is a privation of the good, and a misdirection of our primary longing for God. Thus, sin structures our lives according to surrogate teloi in a kind of parody of creation and reverse-sacramentality. This reverse-sacramentality is now seen at the societal level as passion metastasizes in the institutions that frame so much of our experience of the world.

But the message of the gospel is that God has again hovered over our world and descended into the chaos: first the darkness of the Virgin’s womb, then the darkness and chaos of 1st century Palestine when the God-man walked the earth, and finally into the darkness of the entire world as the Church advances New Creation into every nook and cranny of culture and geography. Through this pattern of descent, divine beauty lifts us heavenward, repairing the broken link between earth and heaven, the material and the spiritual, the sensible and the noetic.

Through repentance we cooperate with God’s new creation energies in speaking life into the non-being of our hearts, in order that the chaos of our disordered souls might become habitable for divine presence. When we engage in this type of creative repentance, we participate not merely in our own healing, but also in the healing of the cosmos.

When things go wrong in our lives—when we get sick, experience poverty, lose our youth, watch loved-ones suffer, lose our jobs to robots, or come face to face with our own looming death—this can lead either to despair or to further voluntary self-emptying as we invite God to hover over our darkness and fill us with His life. In addition to faith and works of charity, that self-emptying may involve everything from breath prayers that reorient our attention back to God, to networks of spiritual mentoring, to monastic retreats, to bodily postures, to liturgical seasons that catch us up in the drama of redemption. At other times, this self-emptying can be as simple as pressing the off switch, or turning your phone to airplane mode. The purpose of all these self-emptying activities is not to negate ourselves but precisely the opposite: to invite God to fill the darkness of our chaotic soul with His divine life, and thus make us more fully ourselves, more fully the man or woman He intends us to be throughout all eternity.

Part of this process of becoming fully ourselves is to embrace limits as good and to live at a humane scale. That is a theme I’ve been exploring here at The Epimethean, with posts about learning to pause, and suggestions on creating a calmer life through going slow. In this quest for a more humane life, I keep coming back to the juxtaposition between Prometheus and his brother, Epimetheus.

I explained the significance of these brothers in the opening essay of this publication, and it is something Joshua highlights in chapter 17 of Are We All Cyborgs Now? That chapter, titled “Three Prophets From the Dawn of the Digital Age,” foregrounds Ivan Illich’s insights from his book Deschooling Society. Here is what Pauling writes in chapter 17 of Are We All Cyborgs Now?:

[Illich] paints an intriguing picture by juxtaposing two figures of Greek mythology: Prometheus and his oft-overlooked brother Epimetheus. For Illich, Prometheus, the one who stole fire from the gods, becomes the symbol of mastery and control, production and manipulation as embodied in society’s technological and institutional structures (whether educational, industrial, economic, political, medical, etc.) There is a valid place for “the Promethean endeavor to forge institutions in order to corral each of the rampant ills,” but in modern society Illich saw “the act of Prometheus carried to an extreme.” While Prometheus’ original infernal theft allowed the shaping of nature and iron, “contemporary man goes further; he attempts to create the world in his image, to build a totally man-made environment, and then discovers that he can do so only on the condition of constantly remaking himself to fit it.” And then the kicker: “we now must face the fact that man himself is at stake.”

Illich, in a somewhat unique interpretive move, sees the forgotten brother Epimetheus as an image of hope. Prometheus (whose name means “forethought”) urges Epimetheus (whose name means “afterthought”) not to marry Pandora (the one who opened the box and let all the evils out—think Eve, Greek-style, whose name means “all-giver”). But Epimetheus marries her anyway, which Illich sees as an act of hope and love, of grace and rootedness. In place of the fiery forge of Prometheus, we have the homely hearth of Epimetheus and Pandora as an example of a life of conviviality and humane scale. Of course, Illich’s commentary fits with another oft-forgotten aspect of this myth: that Pandora closed the lid of the box just in time to keep hope from escaping. Perhaps it was in this simple forging of life together as a family that Epimetheus and Pandora became vessels of that hope. Educational philosopher Richard Kahn is helpful in interpreting: “for Illich, Epimetheus was not the dull-witted brother of Prometheus-the-savior but rather the ancient cultural archetype of those who freely give and recognize gifts, care for and treasure life (especially during times of catastrophe), and attend to the conservation of seeds of hope in the world for future others.”[5] He concludes, “it is Epimetheus who remains freely convivial with the world as given while the progenitor of a new world, Prometheus, remains bound and chained by his own creative deed.”

Illich’s cryptic Epimethean proposal is simple, yet radical, where self-constructions and power relations are replaced with gift and gratitude, grace, and hope. This is more in line with the world as created by the triune God, who gifts the world to mankind, and gifts himself to bring humanity into the very life of God, which is itself an inter-relational self-giving unity of three-in-one.

We can participate in God’s self-giving by making our hearts habitable for God’s presence, so His Spirit can guide us on the journey to our true homeland of perfect beatitude. That journey will be full of perils and hostile creatures, as was Odysseus’s journey. And it will be full of diversions that tempt us with forms of non-being posed as counterfeit beatitude. For Odysseus, diversions came in the form of actual creatures: the sirens, the lotus eaters, the enchantress Circe, and the Nymph Calypso. For us, diversions comes in the form of digital distractions on our phones and laptops, and the larger infrastructures of machine culture that now dominate our lives. And like Odysseus, we run the risk of being lured into passivity and inattention until we forget what is important to us, and what truly matters. Sometimes we need a reminder to get us back on course. When Odysseus lodged too long with Circe, his crew had to remind him to resume his journey. For those of us who have lingered too long in the shadow of the Machine, this book serves as a reminder to resume the journey, and a challenge to stay the course in the pilgrimage to our true homeland, namely the renewed cosmos.

Further Reading

Amazon Listing for Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming Our Humanity From the Machine

“Digital Liturgies: Rediscovering Christian Wisdom in an Online Age,” by Samuel James: A Review

Technology and the Story of Redemption: Being the People of God in a Mechanized World

A Return to Reality – The Path to the Academy Conversations on Orthodoxy and Education